Lung Cancer Is Rising in Non-Smokers. Scientists Are Looking for Causes

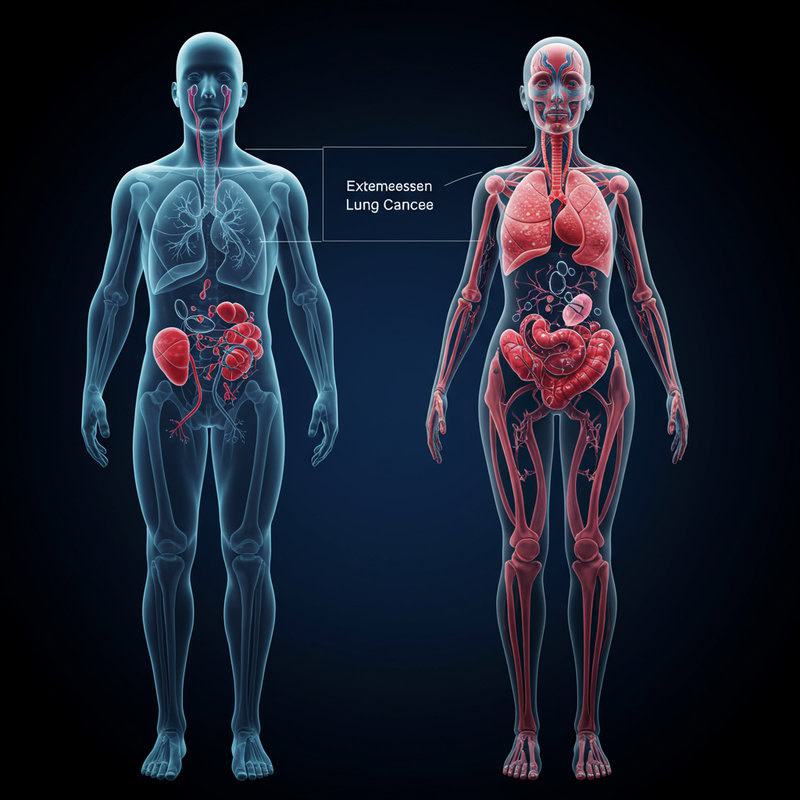

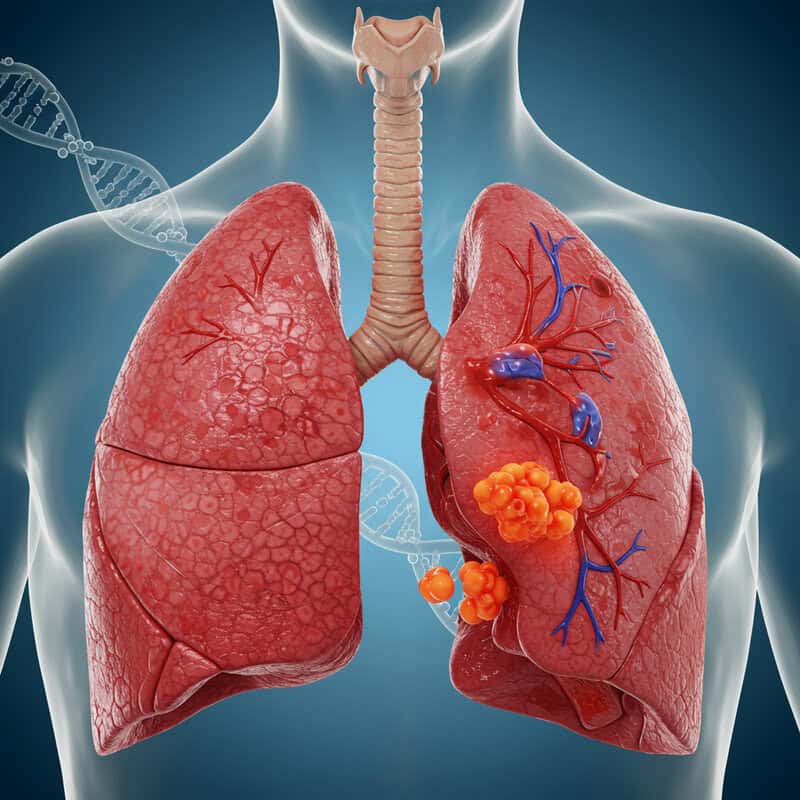

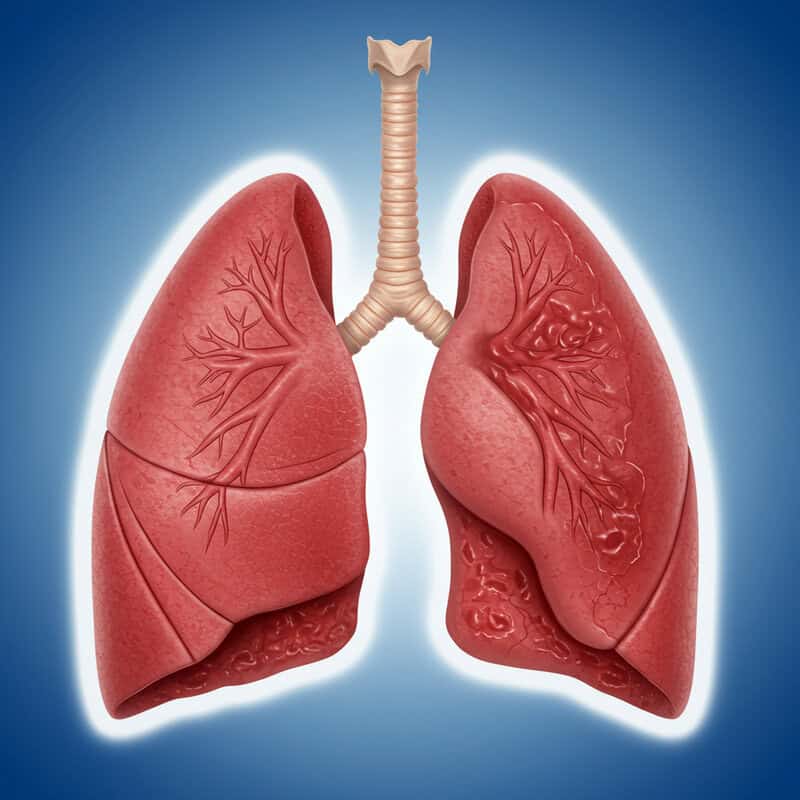

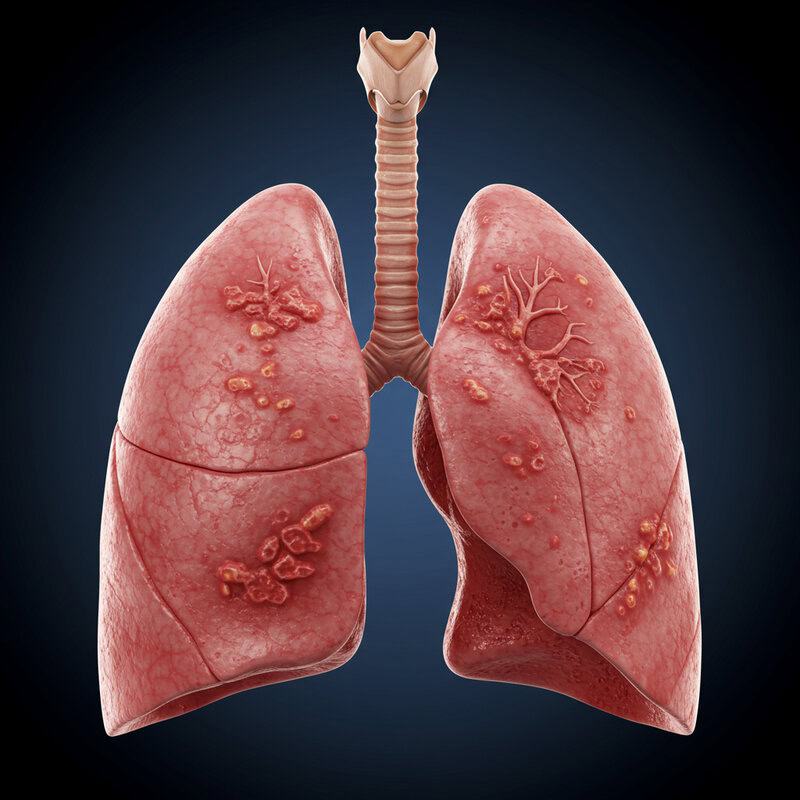

Lung cancer, once predominantly linked to tobacco use, is increasingly affecting individuals who have never smoked. Recent studies show that up to 20% of lung cancer diagnoses in the United States now occur in non-smokers [American Cancer Society]. The disease targets the lungs, vital organs responsible for oxygen exchange. Unfortunately, symptoms often remain hidden until advanced stages, leading to late detection and poorer outcomes. This evolving trend presents a critical challenge for researchers striving to identify new causes and improve early diagnosis for affected populations.

1. Secondhand Smoke Exposure

Secondhand smoke, also known as passive smoke or environmental tobacco smoke, remains a significant risk factor for lung cancer in non-smokers. Inhaling smoke emitted from burning tobacco products or exhaled by smokers exposes non-smokers to many of the same carcinogens as active smoking. Research indicates that individuals living with smokers have a 20-30% greater risk of developing lung cancer compared to those in smoke-free homes [CDC].

The risk is not confined to the household; public spaces where smoking is permitted can also elevate exposure. A landmark study published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated that non-smoking spouses of smokers faced significantly higher lung cancer rates than those with non-smoking partners [NEJM]. Even brief exposures can be harmful, as carcinogens in tobacco smoke linger in the air and on surfaces. The implementation of smoke-free policies in public spaces has helped reduce these risks, but secondhand smoke remains a persistent concern, especially in areas with less regulation or awareness.

2. Air Pollution and Fine Particulates

Air pollution has emerged as a major environmental risk factor for lung cancer, particularly among non-smokers residing in urban areas. The focus is often on fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, which consists of particles with diameters of 2.5 micrometers or less. These tiny particles can penetrate deep into the lungs, bypassing the body’s natural defenses. Numerous studies have established a clear link between elevated PM2.5 levels and increased lung cancer incidence, even among individuals with no history of smoking [World Health Organization].

A comprehensive analysis published in The Lancet found that for every 10 microgram per cubic meter increase in PM2.5, the risk of lung cancer rises by approximately 9% [The Lancet]. Urban populations are particularly vulnerable due to higher concentrations of vehicle emissions, industrial pollutants, and construction dust. Non-smokers in cities with poor air quality may face lung cancer risks comparable to those exposed to secondhand smoke. Efforts to reduce air pollution, such as stricter emission standards and green urban planning, are critical steps in mitigating this growing public health concern.

3. Radon Gas in Homes

Radon is a colorless, odorless, and tasteless radioactive gas that forms naturally from the decay of uranium in soil, rock, and water. It can seep into homes through cracks in floors, walls, and foundations, especially in areas with high natural uranium content. Once inside, radon can accumulate to dangerous levels, posing a significant health risk over time. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified radon as the second leading cause of lung cancer overall, and the leading cause among non-smokers [EPA].

Prolonged exposure to elevated radon levels increases the likelihood of lung cancer, as radioactive particles are inhaled and become trapped in the lungs. According to the World Health Organization, radon is responsible for up to 14% of lung cancer cases globally, with the risk rising in homes where radon levels exceed recommended safety thresholds [World Health Organization]. Testing for radon is the only way to detect its presence indoors, and mitigation systems can effectively reduce concentrations. Raising public awareness and encouraging routine radon testing are crucial steps in protecting non-smokers from this invisible hazard.

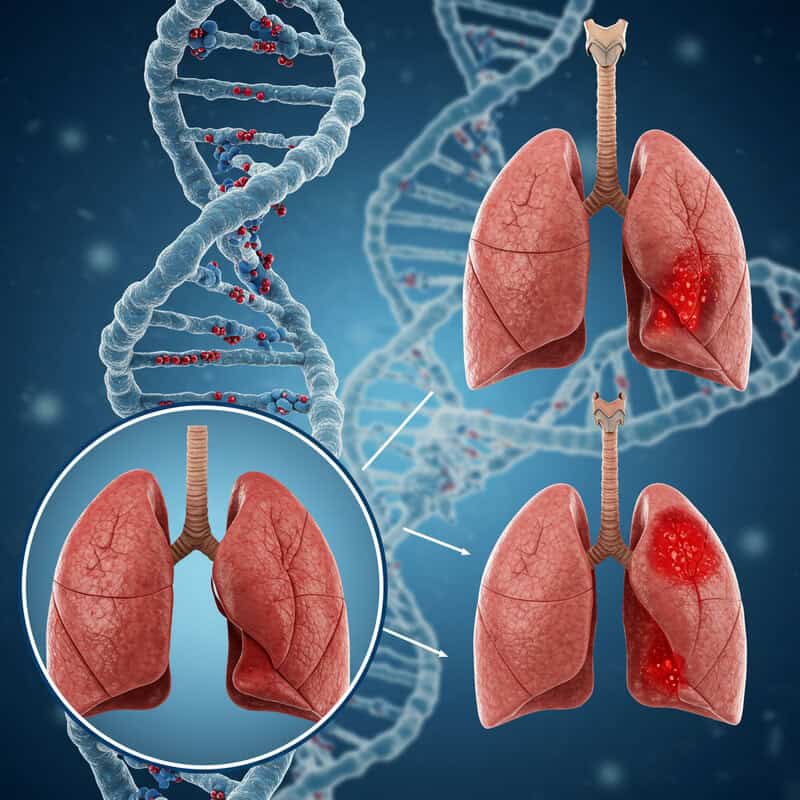

4. Genetic Mutations

While environmental factors play a significant role, inherited genetic mutations can also increase the risk of lung cancer in non-smokers. Certain gene variants, passed down through families, may predispose individuals to develop lung cancer even in the absence of smoking or other obvious environmental causes. For example, mutations in the EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) gene have been found more frequently in lung cancer patients who have never smoked, particularly among women and individuals of East Asian descent [National Cancer Institute].

This genetic susceptibility is similar in concept to the role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in hereditary breast cancer. Just as carriers of BRCA mutations are at increased risk for breast and ovarian cancers, people with certain inherited lung cancer genes may be more vulnerable to the disease regardless of lifestyle factors. Ongoing research is working to identify additional gene variants — such as ALK, ROS1, and TP53 — that contribute to lung cancer risk in non-smokers [American Cancer Society]. Recognizing these genetic factors can help guide targeted screening and personalized treatment strategies for those at greater risk.

5. Occupational Hazards

Workplace exposures to hazardous substances remain a significant, yet sometimes overlooked, cause of lung cancer in non-smokers. Certain industries expose workers to carcinogens such as asbestos, silica dust, and diesel exhaust fumes, all of which have been conclusively linked to an increased risk of lung cancer. Asbestos, once widely used in construction and manufacturing, releases microscopic fibers that can be inhaled and cause cellular damage over time. Even decades after exposure, the risk of lung cancer persists [National Cancer Institute].

Silica, commonly encountered in mining, quarrying, and construction, poses a similar danger. Inhalation of silica dust leads to lung inflammation and scarring, increasing cancer risk [OSHA]. Diesel exhaust, prevalent in transportation, warehousing, and heavy equipment operation, contains a mixture of gases and particulates recognized as carcinogenic by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [American Cancer Society]. Workers in these and related industries face higher lung cancer risks, even if they have never smoked. Implementing strict workplace safety standards, such as improved ventilation, protective equipment, and regular health monitoring, is crucial to reduce occupational lung cancer risk among non-smokers.

6. Indoor Cooking Fumes

Indoor air pollution from cooking is a significant but underappreciated risk factor for lung cancer in non-smokers, particularly in regions where solid fuels like wood, coal, or biomass are commonly used. Burning these fuels in stoves without adequate ventilation releases a variety of harmful substances, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter, which can be inhaled by household members. Studies have shown that prolonged exposure to these emissions significantly raises lung cancer risk, especially among women responsible for cooking in many cultures [World Health Organization].

Even in homes using modern fuels like gas or electricity, high-heat cooking methods such as stir-frying with certain oils can generate hazardous fumes. Research published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention found that fumes from heated oils, particularly during deep-frying, contain carcinogenic compounds that persist in the air of poorly ventilated kitchens [Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention]. Lack of exhaust fans or open windows exacerbates the risk by trapping pollutants indoors. Raising awareness about the importance of kitchen ventilation and adopting safer cooking practices are vital steps in reducing this overlooked source of lung cancer risk among non-smokers.

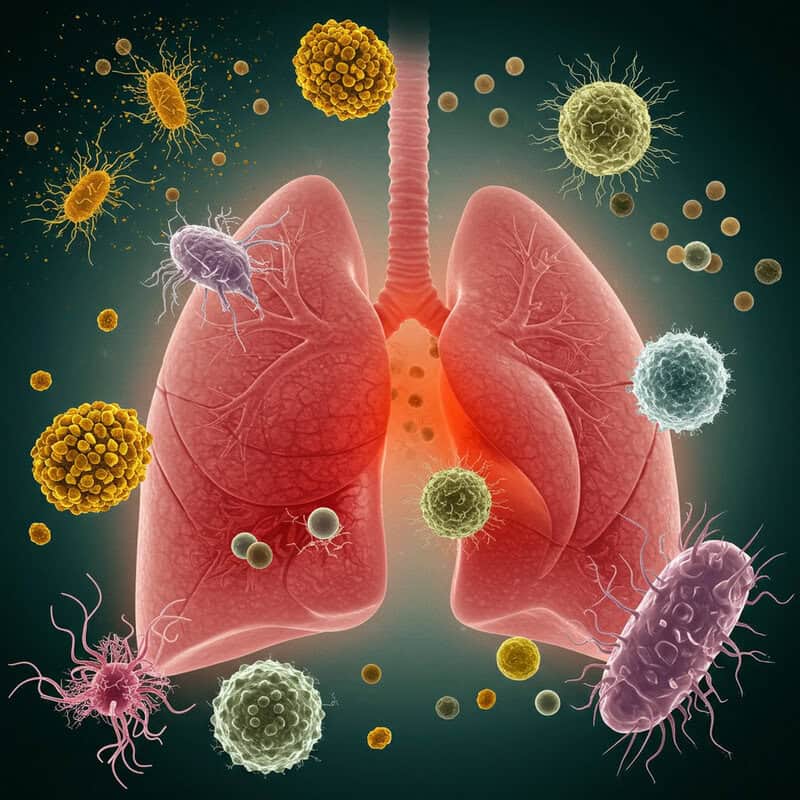

7. Viral Infections (HPV, EBV)

Certain viral infections have been implicated in the development of lung cancer among non-smokers. Notably, the human papillomavirus (HPV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) are capable of altering cellular DNA, setting the stage for malignant transformation. HPV, most commonly associated with cervical and other anogenital cancers, has also been detected in lung tumor tissues, particularly in non-smokers and populations from East Asia [National Institutes of Health]. These viruses can integrate their genetic material into host cells, disrupting normal cell cycle regulation and promoting uncontrolled growth.

Epstein-Barr virus, best known for causing infectious mononucleosis, is also linked to a range of cancers, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma and some lymphomas. Recent research suggests EBV infection may contribute to specific subtypes of lung cancer, particularly in non-smokers [NIH]. By inducing chronic inflammation and directly interfering with DNA repair mechanisms, these viruses can increase the likelihood of mutations that drive cancer development. Continued investigation into the role of viral infections in lung carcinogenesis could lead to new strategies for prevention, early detection, and targeted therapies for non-smokers at risk.

8. Pre-existing Lung Diseases

Chronic lung diseases can increase the susceptibility of non-smokers to lung cancer by creating an environment of persistent inflammation and tissue damage. Conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and pulmonary fibrosis alter the structure and function of lung tissue, making it more prone to malignant transformation. Even in individuals without a history of tobacco use, these diseases foster cellular stress and repeated cycles of injury and repair, heightening the risk for genetic mutations that can lead to cancer [National Cancer Institute].

COPD, which includes chronic bronchitis and emphysema, is typically associated with smoking but can also develop due to long-term exposure to air pollutants or genetic factors. Pulmonary fibrosis, characterized by scarring of lung tissue, is linked to various environmental triggers and autoimmune conditions. Both diseases are recognized as independent risk factors for lung cancer, with studies showing that individuals with COPD face up to a four-fold increased risk, even after controlling for smoking status [NIH]. Understanding the interplay between chronic lung diseases and cancer is essential for early surveillance and intervention, particularly among vulnerable non-smoker populations.

9. Hormonal Factors

Emerging research suggests that hormonal factors, particularly estrogen, may play a significant role in lung cancer development among non-smokers, especially women. Estrogen receptors have been found in many lung cancer tissues, indicating that this hormone could influence tumor growth and progression. Studies have shown that women who have never smoked are more likely to develop certain types of lung cancer, such as adenocarcinoma, compared to men, raising questions about the interplay between female hormones and cancer risk [National Cancer Institute].

The use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and oral contraceptives has also been investigated for its potential impact on lung cancer risk. Some findings indicate that long-term use of estrogen-containing therapies may increase susceptibility to lung cancer, while others suggest a protective effect, highlighting the complexity of the relationship [NIH]. Researchers believe that estrogen may promote cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis, processes that can facilitate the development and growth of tumors. Further studies are needed to clarify the precise mechanisms and to determine whether modifying hormone exposure could reduce lung cancer risk among women who have never smoked.

10. Family History and Heredity

A family history of lung cancer is a well-documented risk factor that can elevate an individual’s likelihood of developing the disease, even in the absence of direct smoking exposure. Research indicates that people with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) diagnosed with lung cancer are at a significantly higher risk compared to those without such a history [American Cancer Society]. This increased risk persists for non-smokers, suggesting that genetic predispositions, shared environmental exposures, or a combination of both may be at play.

Genetic studies have identified several inherited mutations that may contribute to familial lung cancer, including alterations in genes involved in cell growth, DNA repair, and carcinogen metabolism. For example, variations in the TP53 and EGFR genes are more frequently observed among individuals with a family history of the disease [PubMed]. While the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, these findings underscore the importance of recognizing family history as a risk factor. Non-smokers with a familial link to lung cancer may benefit from earlier and more frequent screenings, as well as genetic counseling to better understand their personal risk.

11. Diet and Nutrition

Dietary habits have a notable impact on lung cancer risk, even among individuals who have never smoked. Numerous studies suggest that a diet low in fruits and vegetables, which are rich in antioxidants and phytochemicals, may increase susceptibility to lung cancer. Antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E, and beta-carotene help neutralize free radicals and reduce cellular damage, potentially lowering cancer risk [NIH]. Conversely, inadequate intake of these nutrients can leave lung tissue more vulnerable to environmental carcinogens and inflammation.

High consumption of processed meats, such as bacon, sausages, and deli meats, has also been linked to elevated lung cancer risk. These foods often contain nitrates and nitrites, which can form carcinogenic compounds during digestion. A meta-analysis published in the journal PLoS One found that higher processed meat intake was associated with a greater risk of lung cancer, independent of smoking status [PLoS One]. Overall, a balanced diet emphasizing fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins may help protect non-smokers from lung cancer, while reducing processed meat consumption is a prudent preventive measure.

12. Environmental Carcinogens (Arsenic, Chromium)

Exposure to environmental carcinogens, such as arsenic and chromium, represents a significant but often underrecognized risk factor for lung cancer in non-smokers. Arsenic, a naturally occurring element, can contaminate groundwater in certain regions, particularly through wells in rural areas. Chronic ingestion of arsenic-laden water has been linked to an increased risk of various cancers, including lung cancer, even at low to moderate concentrations [CDC]. This toxic element interferes with cellular processes and promotes DNA mutations and oxidative stress, contributing to carcinogenesis.

Chromium, especially in its hexavalent form (chromium VI), is another potent carcinogen found in soil and industrial pollutants. Occupational exposure, as well as environmental contamination from manufacturing or improper waste disposal, can lead to inhalation or ingestion of chromium compounds. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified chromium VI as a known human carcinogen, with studies linking it to an increased incidence of lung cancer among exposed populations [IARC]. Reducing exposure to these environmental toxins through improved water filtration, soil remediation, and stricter industrial regulations is vital for lowering lung cancer risk among non-smokers.

13. Passive Vaping and E-cigarettes

As the popularity of e-cigarettes and vaping devices has surged, concerns have arisen about the potential health risks of passive exposure to their aerosols, particularly for non-smokers. Unlike traditional tobacco smoke, vaping aerosols contain a mixture of nicotine, flavorings, solvents such as propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin, and a host of chemical byproducts created during heating. Studies have shown that passive exposure to these aerosols can deliver nicotine and ultrafine particles to bystanders, raising questions about their long-term effects on lung health [CDC].

Although research into the carcinogenic potential of secondhand vaping is still in its early stages, initial findings are cause for concern. Some e-cigarette aerosols contain formaldehyde, acrolein, and heavy metals, all of which are known or suspected lung carcinogens [American Lung Association]. Because vaping is a relatively new phenomenon, the cumulative effects of chronic, low-level exposure remain largely unknown, especially in vulnerable populations such as children and people with pre-existing lung conditions. Ongoing research and regulatory oversight are critical to better understand and mitigate the possible risks of passive vaping for non-smokers.

14. Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a driving factor in the development of various cancers, including lung cancer among non-smokers. Persistent inflammation in the lungs may arise from autoimmune conditions—such as rheumatoid arthritis or lupus—or from ongoing allergic reactions, including asthma or chronic bronchitis. During inflammation, immune cells release cytokines and reactive oxygen species that can inadvertently damage lung tissue and DNA over time [National Cancer Institute].

This repeated cycle of injury and repair increases the likelihood of genetic mutations and cellular misregulation, setting the stage for malignant transformation. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with chronic lung inflammation face a higher risk of lung cancer, independent of tobacco exposure [NIH]. The mechanisms behind this association involve both direct DNA damage and the creation of a microenvironment that encourages abnormal cell growth. Effective management of autoimmune and allergic diseases, along with minimizing exposure to environmental irritants, can help reduce the risk of inflammation-driven lung cancer in non-smokers. Further research is essential to develop targeted therapies that address the inflammatory pathways implicated in cancer development.

15. Ionizing Radiation

Ionizing radiation is a well-established risk factor for the development of lung cancer, even among individuals with no tobacco exposure. This type of radiation carries enough energy to damage DNA within lung cells, increasing the likelihood of mutations that can initiate cancer. Sources of ionizing radiation include certain medical imaging procedures, such as repeated chest X-rays or computed tomography (CT) scans, as well as therapeutic radiation treatments for other cancers [National Cancer Institute].

Environmental exposure also poses significant risks, with radon gas being a prime example of naturally occurring ionizing radiation (as discussed previously). Additionally, individuals who have lived or worked in areas affected by nuclear accidents or who have occupational exposure to radioactive materials are at increased risk. The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies ionizing radiation as a Group 1 carcinogen, indicating sufficient evidence of its cancer-causing potential in humans [IARC]. While the benefits of diagnostic imaging often outweigh the risks, it is essential for healthcare providers to minimize unnecessary exposure and for individuals to be aware of environmental sources of radiation that could elevate lung cancer risk over time.

16. Urbanization and Population Density

Urbanization and high population density are increasingly recognized as contributors to rising lung cancer rates among non-smokers. Residents of densely populated cities are exposed to a complex mix of risk factors, including elevated levels of air pollution, industrial emissions, and vehicle exhaust. These environmental hazards, particularly fine particulate matter (PM2.5), are more prevalent and concentrated in urban settings, directly impacting lung health [World Health Organization].

Beyond pollution, city living often correlates with lifestyle factors that can compound cancer risk. Limited access to green spaces, increased stress, and higher rates of sedentary behavior are all associated with urban environments. Additionally, crowded housing and workplace conditions may heighten exposure to secondhand smoke, indoor pollutants, and infectious agents. Studies, such as those published in Environmental Health Perspectives, have highlighted a greater incidence of lung cancer in metropolitan areas compared to rural regions, even after controlling for tobacco exposure [Environmental Health Perspectives]. Addressing the unique challenges posed by urbanization—through improved air quality regulations, urban planning, and public health initiatives—is essential for reducing lung cancer risk in non-smoking city dwellers.

17. Occupational Diesel Exhaust

Occupational exposure to diesel exhaust is a significant risk factor for lung cancer, especially among truck drivers, heavy equipment operators, railroad workers, and others who spend extended periods in environments with high concentrations of diesel fumes. Diesel exhaust contains a mix of gases and tiny particles, many of which are classified as carcinogenic. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified diesel engine exhaust as a Group 1 carcinogen, indicating there is sufficient evidence linking it to lung cancer in humans [IARC].

Studies have shown that workers with prolonged exposure to diesel exhaust have a significantly elevated risk of developing lung cancer compared to those in less polluted occupational settings. The carcinogenic potential is attributed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other chemicals found in diesel soot, which can be inhaled deeply into the lungs and cause DNA damage over time [American Cancer Society]. Implementing protective measures, such as improved vehicle emission standards, use of personal protective equipment, and better ventilation in workspaces, is critical to safeguard the health of workers regularly exposed to diesel fumes and reduce lung cancer risk among non-smokers.

18. Age-Related Changes

Age is one of the most significant risk factors for cancer, including lung cancer in non-smokers. As individuals age, the cumulative number of cell divisions and natural wear and tear on the body increase the likelihood of genetic mutations. Over time, the body’s ability to repair damaged DNA diminishes, and the immune system’s efficiency in identifying and eliminating abnormal cells declines [National Cancer Institute]. This age-related vulnerability means that even in the absence of traditional risk factors such as smoking, older adults face a greater risk of developing lung cancer.

The majority of lung cancer cases—among both smokers and non-smokers—are diagnosed in people over the age of 65. Research suggests that age-related changes, such as increased oxidative stress and chronic inflammation, contribute to the accumulation of cellular damage that can lead to malignancy [NIH]. Additionally, the longer a person lives, the more opportunities there are for environmental exposures and random genetic errors to accumulate. Understanding the intersection of aging and cancer risk underscores the importance of regular screening and vigilance for early symptoms, even among non-smokers as they grow older.

19. Gender Differences

Research has revealed notable gender differences in lung cancer susceptibility, with women—especially non-smokers—being more prone to certain types of lung cancer than men. Epidemiological data show that women are more likely to develop lung adenocarcinoma, the most common form of lung cancer among non-smokers [National Cancer Institute]. Several biological and hormonal factors appear to contribute to this disparity. For example, estrogen receptors are frequently found in lung tumor tissues, and estrogen is believed to promote tumor growth and progression. This may help explain why women are more susceptible to lung cancer in the absence of smoking.

Genetic factors also play a role: mutations in the EGFR gene are more common in female non-smokers with lung cancer, particularly among Asian women [NIH]. Additionally, differences in immune response and metabolism of carcinogens may further increase risk in women. Environmental exposures, such as indoor cooking fumes, have a disproportionate effect on women in many cultures, compounding their vulnerability. Understanding these gender differences is crucial for developing tailored prevention, screening, and treatment strategies that address the unique risks faced by women who have never smoked.

20. Ethnic and Genetic Background

Ethnic and genetic background significantly influence lung cancer susceptibility among non-smokers. Research has shown that certain populations, particularly East Asians, have a higher incidence of lung cancer in the absence of tobacco exposure. A key factor in this disparity is the prevalence of mutations in the EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) gene, which is much more common in East Asian non-smokers diagnosed with lung adenocarcinoma than in their Western counterparts [NIH]. These genetic alterations drive tumor growth and are believed to arise independently of environmental triggers such as smoking.

Other populations also exhibit differences in lung cancer risk due to variations in genes involved in DNA repair, carcinogen metabolism, and immune response. For example, certain genetic polymorphisms found in African American and Hispanic populations may impact susceptibility and disease progression [National Cancer Institute]. Understanding these ethnic and genetic differences is critical for developing effective targeted therapies and personalized prevention strategies. Genetic testing for mutations such as EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 can guide treatment choices and improve outcomes for non-smoking lung cancer patients from diverse backgrounds.

21. Pre-existing Autoimmune Disorders

Individuals with autoimmune disorders, such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren’s syndrome, are at increased risk for developing lung cancer—even in the absence of traditional risk factors like smoking. Autoimmune diseases are characterized by the immune system attacking the body’s own tissues, leading to chronic inflammation and repeated cycles of cellular injury and repair. This persistent inflammation in the lungs can result in DNA mutations and a microenvironment conducive to cancer development [NIH].

Lupus, specifically, has been associated with an elevated risk of various cancers, including lung cancer. Studies suggest that both the disease process and the immunosuppressive medications often used to manage autoimmune conditions may contribute to this vulnerability [National Cancer Institute]. Immunosuppressive therapies can impair immune surveillance, reducing the body’s ability to detect and eliminate abnormal cells before they become cancerous. Furthermore, the chronic inflammation caused by autoimmune activity can accelerate genetic damage within lung tissue. For non-smokers living with autoimmune diseases, regular monitoring and early screening are crucial for timely detection of lung cancer and improved outcomes.

22. Diesel and Gasoline Emissions

Traffic-related air pollution, stemming from diesel and gasoline vehicle emissions, is a growing public health concern and a notable risk factor for lung cancer in non-smokers. Unlike occupational exposures, which primarily affect workers in certain industries, community-wide exposure to vehicular emissions impacts vast urban and suburban populations. Diesel and gasoline exhaust both contain hazardous substances such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, benzene, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), all of which are recognized carcinogens [American Cancer Society].

Living or working near busy roads, highways, or major transportation hubs increases the likelihood of inhaling these harmful pollutants. Studies have shown that people residing in areas with high levels of traffic-related air pollution face an elevated risk of lung cancer, even after accounting for smoking status and occupational hazards [NIH]. Children, the elderly, and those with pre-existing health conditions are especially vulnerable. Reducing traffic emissions through clean vehicle technologies, promoting public transportation, and implementing stricter air quality regulations are vital strategies to lower lung cancer risk in non-smokers exposed to urban and suburban traffic pollution.

23. Chronic Respiratory Infections

Repeated or chronic respiratory infections, such as tuberculosis (TB), bronchitis, or pneumonia, can contribute to an increased risk of lung cancer in non-smokers. Persistent infections often result in ongoing inflammation, tissue damage, and cycles of repair that create a favorable environment for DNA mutations and abnormal cell growth. Tuberculosis, in particular, has been strongly linked to lung cancer development; the scarring and fibrotic changes left by TB infections can predispose lung tissue to malignant transformation decades after the initial infection [NIH].

Research published in the journal Lung Cancer found that individuals with a history of TB infection had up to a two-fold higher risk of developing lung cancer compared with those without such a history [Lung Cancer Journal]. The mechanisms are thought to involve chronic inflammation, immune dysregulation, and the direct effects of scarring on cellular architecture. Other chronic lung infections, such as those caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria or recurrent bacterial pneumonias, may also contribute to increased cancer risk. Recognizing and managing chronic respiratory infections promptly is essential for reducing long-term lung cancer risk, particularly among non-smokers.

24. Early-Life Exposure to Pollutants

Exposure to air pollution and environmental toxins during childhood can have long-lasting effects on lung health and significantly increase the risk of lung cancer later in life, even among non-smokers. The developing lungs of children are particularly sensitive to pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide, and volatile organic compounds, which can impair proper lung growth and function [World Health Organization]. Early-life exposure to secondhand smoke, household chemicals, and industrial emissions can result in chronic inflammation and structural changes in lung tissue, laying the foundation for future disease.

Research published in The Lancet Planetary Health has shown that children who grow up in highly polluted environments are more likely to experience reduced lung capacity, respiratory illnesses, and an increased risk of respiratory cancers as adults [The Lancet Planetary Health]. These effects are compounded by prolonged exposure and can be exacerbated by socioeconomic factors, such as limited access to healthcare and safe housing. Preventing early-life exposure to environmental pollutants through cleaner air policies and public health interventions is critical to reducing the lifetime risk of lung cancer in non-smokers.

25. Poor Indoor Air Quality

Poor indoor air quality is an often overlooked contributor to lung cancer risk, particularly in non-smokers who spend significant time indoors. Common indoor pollutants include mold spores, dust mites, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released from household products like cleaning agents, paints, and air fresheners. Prolonged exposure to these contaminants can lead to chronic lung irritation, inflammation, and potentially DNA damage, increasing the likelihood of malignant transformation in lung tissues [EPA].

Mold growth, especially in damp environments, produces mycotoxins that are known to cause respiratory issues and may be linked to cancer risk, although more research is needed to fully understand this relationship. Fine dust particles can penetrate deep into the lungs, carrying allergens, bacteria, and chemical residues that contribute to chronic inflammation. VOCs, such as formaldehyde and benzene, have been classified as carcinogens and are frequently detected at higher levels indoors than outdoors [American Cancer Society]. Improving ventilation, controlling humidity, and reducing the use of chemical-laden products are essential steps in minimizing indoor air pollution and lowering lung cancer risk for non-smokers.

26. Lack of Physical Activity

A sedentary lifestyle is emerging as an indirect risk factor for lung cancer among non-smokers. Regular physical activity has been shown to support healthy lung function, reduce inflammation, and boost immune surveillance, all of which help protect against cancer development. In contrast, prolonged inactivity can contribute to systemic inflammation, impaired lung capacity, and increased vulnerability to respiratory infections and chronic diseases [NIH].

Several studies have found a correlation between low levels of physical activity and higher incidence of lung cancer, independent of smoking status. Physical inactivity can also lead to obesity and metabolic dysfunction, both of which are associated with chronic inflammation and oxidative stress—key processes in carcinogenesis. According to the American Cancer Society, moderate to vigorous exercise may lower the risk of developing certain types of lung cancer by enhancing respiratory health and reducing harmful inflammatory markers [American Cancer Society]. Encouraging regular exercise, even simple activities like walking or cycling, is a practical and effective strategy to help lower lung cancer risk and promote overall well-being in non-smokers.

27. Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome

Obesity and metabolic syndrome are increasingly recognized as contributors to lung cancer risk, even among non-smokers. Excess body weight is associated with chronic, systemic inflammation, which can promote the development and progression of various cancers, including those affecting the lungs. Adipose tissue in obese individuals secretes inflammatory cytokines and hormones that can disrupt normal cell regulation, increase oxidative stress, and impair immune surveillance [National Cancer Institute].

Metabolic syndrome—a cluster of conditions including obesity, insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and abnormal cholesterol levels—further amplifies these risks. Research published in JAMA Oncology has demonstrated a link between metabolic syndrome and elevated lung cancer incidence in non-smokers [JAMA Oncology]. The mechanisms are thought to involve increased levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors, which can stimulate abnormal cell proliferation. Additionally, the pro-inflammatory environment associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome can facilitate DNA damage and tumorigenesis. Addressing obesity through dietary changes, regular physical activity, and management of metabolic risk factors is crucial for reducing lung cancer risk in the non-smoking population.

28. Alcohol Use

The relationship between alcohol consumption and lung cancer risk in non-smokers has been the subject of ongoing scientific debate. While heavy alcohol use is well established as a risk factor for several cancers, including those of the mouth, throat, and liver, its direct association with lung cancer remains less clear, especially in individuals who have never smoked. Some studies suggest a modest increase in lung cancer risk with high levels of alcohol intake, potentially due to the carcinogenic effects of acetaldehyde, a toxic metabolite of alcohol that can damage DNA and promote cell mutations [National Cancer Institute].

Other research, however, has found no significant association between moderate alcohol use and lung cancer in non-smokers, highlighting the challenges in isolating alcohol’s effects from confounding factors such as passive smoke exposure or occupational hazards [NIH]. It is possible that the risk is more pronounced when alcohol use is combined with other carcinogenic exposures. Although the evidence is not conclusive, adopting a cautious approach to alcohol consumption is generally recommended for overall cancer prevention and health, particularly for those already at increased risk due to genetic or environmental factors.

29. Vitamin and Mineral Deficiencies

Deficiencies in key vitamins and minerals—particularly vitamins A, C, and E—may compromise the body’s natural defenses against lung cancer, even in non-smokers. These nutrients function as antioxidants, helping to protect lung tissue from oxidative damage caused by free radicals and environmental pollutants. Vitamin A plays a crucial role in maintaining healthy epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract, while vitamins C and E neutralize harmful reactive oxygen species, potentially reducing inflammation and DNA mutations [NIH Office of Dietary Supplements].

Several epidemiological studies have suggested that low dietary intake or blood levels of these vitamins are associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. For instance, research published in the International Journal of Cancer found that individuals with higher intakes of vitamin C and E had a lower risk of lung cancer, independent of smoking status [International Journal of Cancer]. However, supplementation with high doses of certain vitamins, particularly beta-carotene, has not consistently shown protective effects and may even increase risk in some populations. The consensus supports obtaining these nutrients through a balanced diet rich in fruits and vegetables to help maintain optimal lung health.

30. Chemotherapy and Radiation from Past Cancers

Individuals who have undergone treatment for other cancers, particularly involving chest radiation or specific chemotherapeutic agents, face an increased risk of developing lung cancer later in life—even if they have never smoked. Chest radiation, commonly used to treat lymphoma, breast cancer, and certain pediatric malignancies, can cause cumulative DNA damage in healthy lung tissue, raising the likelihood of malignant transformation over time [American Cancer Society]. The risk is especially pronounced for those treated at a younger age or with higher radiation doses.

Certain chemotherapy drugs, such as alkylating agents, are also associated with an elevated risk of secondary cancers, including lung cancer. According to studies published in The Lancet Oncology, survivors of childhood and young adult cancers treated with both chemotherapy and radiation have a significantly higher long-term risk of lung cancer compared to the general population [The Lancet Oncology]. Regular follow-up and screening are essential for cancer survivors, enabling early detection and intervention. Awareness of these risks helps inform treatment decisions and long-term health monitoring strategies for individuals with a history of cancer therapy.

31. Use of Biomass Fuels

The use of biomass fuels—such as wood, animal dung, and coal—for heating and cooking poses a significant health risk, particularly in developing regions where cleaner energy alternatives are limited. Burning these fuels in open fires or traditional stoves releases a variety of hazardous substances, including fine particulate matter (PM2.5), carbon monoxide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and volatile organic compounds. Prolonged inhalation of these pollutants can lead to chronic respiratory irritation, inflammation, and an increased risk of lung cancer, even among individuals who have never smoked [World Health Organization].

Women and children are disproportionately affected, as they often spend more time near indoor fires in poorly ventilated homes. Studies have shown that household air pollution from biomass combustion is a leading environmental cause of lung cancer deaths in low- and middle-income countries [NIH]. Interventions such as the adoption of cleaner cookstoves, use of alternative fuels, and improvements in household ventilation can dramatically reduce exposure to carcinogenic emissions. Raising awareness and investing in sustainable energy solutions are critical for protecting vulnerable populations from the hidden dangers of biomass fuel use.

32. Prior Chest Infections

Severe chest infections, such as pneumonia or pleurisy, can have long-term implications for lung health, even after apparent recovery. These infections can cause significant inflammation and may result in lasting scarring or fibrosis of lung tissue. This scarring disrupts the normal architecture of the lungs, creating areas where abnormal cell growth is more likely to occur. Over time, these changes can increase the risk of lung cancer, particularly among non-smokers who lack other major risk factors [NIH].

Research has shown that individuals with a history of severe or recurrent chest infections are more likely to develop lung cancer later in life. For example, a large study published in the European Respiratory Journal found a significant association between past pneumonia and an increased incidence of lung cancer, independent of smoking status [European Respiratory Journal]. The underlying mechanism is thought to involve chronic inflammation, repeated cycles of tissue damage and repair, and genetic mutations in the affected areas. Preventing and promptly treating chest infections, as well as monitoring lung health after severe illness, are important steps to reduce long-term cancer risk in non-smokers.

33. Use of Certain Medications

Some medications, when used long-term or in high doses, may contribute to lung cancer risk in non-smokers by causing lung tissue damage or interfering with cellular repair mechanisms. Chemotherapeutic agents, such as alkylating agents and certain targeted therapies, are well-documented for their potential to induce secondary malignancies, including lung cancer, due to their direct effects on DNA and cell division [National Cancer Institute]. Additionally, drugs used to treat autoimmune conditions, such as immunosuppressants and biologics, can impair immune surveillance, making it harder for the body to eliminate precancerous or cancerous cells.

Some antiarrhythmic medications, notably amiodarone, and certain antibiotics have been associated with lung toxicity and chronic pulmonary inflammation, which may elevate cancer risk over time [NIH]. Corticosteroids, when used chronically, suppress immune function and may contribute indirectly to carcinogenesis by reducing the body’s natural defenses. While these medications are essential for managing serious health conditions, regular monitoring and risk-benefit assessments are crucial. Patients should discuss any long-term medication use with their healthcare providers to ensure lung health is protected and to facilitate early detection of potential complications.

34. Geographic Location

Where someone lives can significantly influence their risk of developing lung cancer as a non-smoker, due to environmental exposures unique to certain geographic regions. In areas with high natural radon levels—such as the northern United States, parts of Canada, and many regions in Eastern Europe—residents are at increased risk, as radon is a radioactive gas that seeps from the ground and accumulates in homes, often without detection [EPA]. Prolonged exposure to elevated radon concentrations can damage lung tissue at the cellular level, making geographic location a critical risk factor.

Air pollution is another regionally variable risk factor. Urban and industrialized areas with persistent smog, vehicle emissions, and industrial pollutants—such as cities in China, India, and other rapidly developing nations—report higher lung cancer rates among non-smokers [World Health Organization]. The combination of high population density, poor air quality, and sometimes limited access to healthcare can significantly elevate risk. For residents of these regions, regular lung health monitoring, household radon testing, and advocacy for cleaner air policies are important steps in reducing the environmentally driven burden of lung cancer.

35. Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) plays a significant role in lung cancer risk among non-smokers, influencing both exposure to environmental hazards and access to preventive healthcare. Individuals with lower income and education levels are more likely to reside in areas with higher air pollution, substandard housing, and increased exposure to indoor pollutants such as mold, radon, and secondhand smoke [CDC]. They may also rely on biomass fuels for cooking and heating, further elevating their risk.

Lower SES is frequently associated with limited access to healthcare resources, meaning early detection and treatment of lung cancer may be delayed, resulting in poorer outcomes. Preventive measures, such as regular medical checkups, radon testing, and public health education, may be less accessible or prioritized in low-income communities. Research published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention has shown that socioeconomic disparities persist in lung cancer incidence and survival, even after adjusting for smoking status [Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention]. Addressing these inequalities through targeted interventions, improved access to care, and public health initiatives is essential for reducing lung cancer risk and improving outcomes among non-smokers in disadvantaged populations.

36. Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression significantly increases the risk of lung cancer among non-smokers by weakening the body’s natural defense mechanisms against abnormal cell growth and malignancy. Individuals receiving immunosuppressive drugs—such as organ transplant recipients or patients with autoimmune diseases—are less able to detect and destroy precancerous or cancerous cells. Long-term use of medications like corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or biologics can impair immune surveillance, allowing cancerous changes in lung tissue to go unchecked [National Cancer Institute].

People living with HIV/AIDS are also at an elevated risk for lung cancer, independent of smoking status. Their compromised immune systems struggle to control infections and cellular abnormalities, leading to a higher incidence of various cancers, including those of the lung [American Cancer Society]. Studies have shown that lung cancer often occurs at a younger age and progresses more rapidly in immunosuppressed populations. Enhanced cancer screening, early intervention, and careful management of immunosuppressive therapy are essential strategies to mitigate lung cancer risk among those with chronic immune system suppression, regardless of smoking history.

37. Personal History of Cancer

Individuals who have survived other cancers face an elevated risk of developing lung cancer later in life, even if they have never smoked. This increased vulnerability is often due to a combination of factors, including genetic predispositions, shared risk factors, and the effects of previous cancer treatments. Radiation therapy to the chest area for cancers such as breast, lymphoma, or esophageal cancer can cause long-term damage to lung tissue, increasing the likelihood of malignant transformation [National Cancer Institute].

Additionally, certain chemotherapy agents are known to raise the risk of secondary cancers, including those of the lung, by inducing DNA mutations or suppressing the immune system. Underlying genetic mutations, such as BRCA or TP53, can also predispose individuals to multiple cancer types, making cancer survivors inherently more susceptible [American Cancer Society]. Survivors may also be more likely to undergo regular medical imaging, which, if excessive, can expose them to additional ionizing radiation. Given these risks, routine follow-up care and lung cancer screening are particularly important for cancer survivors, helping ensure early detection and improved outcomes for this high-risk group.

38. Use of Traditional Medicines

The use of traditional medicines and herbal remedies is common in many cultures, but some of these treatments may unwittingly increase the risk of lung cancer in non-smokers. Certain herbs and natural compounds have been found to contain carcinogenic ingredients, such as aristolochic acids, which are present in some traditional Chinese medicines and have been linked to various cancers, including those of the respiratory tract [National Cancer Institute]. In addition, some herbal preparations may be contaminated with heavy metals (arsenic, lead) or environmental toxins due to poor regulation and quality control.

The risks are not limited to ingestion. The burning of certain herbs or animal products for inhalation or fumigation in traditional practices can release carcinogenic smoke and particulates, directly affecting lung tissue. Studies have also raised concerns about the adulteration of herbal products with pharmaceuticals or synthetic chemicals, which may have harmful, long-term effects [NIH]. Consumers should exercise caution, seek products from reputable sources, and consult healthcare professionals before using any traditional medicines, especially those with known or suspected carcinogenic properties, to reduce inadvertent lung cancer risk.

39. Chronic Stress

Chronic psychological stress is increasingly recognized as an indirect factor that may influence cancer risk, including lung cancer in non-smokers. Prolonged stress can disrupt the body’s hormonal balance and suppress immune function, making it more difficult for the immune system to detect and eliminate abnormal or precancerous cells. Elevated levels of stress hormones, such as cortisol and adrenaline, promote systemic inflammation and may alter cellular environments in ways that favor carcinogenesis [National Cancer Institute].

While stress itself is not a direct carcinogen, it can contribute to unhealthy coping behaviors—such as poor diet, lack of exercise, disrupted sleep, and increased exposure to environmental risks—which further elevate cancer susceptibility. Research published in Frontiers in Oncology highlights how chronic stress can impair DNA repair mechanisms and reduce the effectiveness of immune surveillance against tumor cells [Frontiers in Oncology]. Addressing chronic stress through psychological support, mindfulness, and healthy lifestyle choices is an important—though often overlooked—component of comprehensive cancer prevention, particularly for non-smokers who may already be at risk due to other environmental or genetic factors.

40. Low Awareness and Delayed Diagnosis

One of the most significant challenges facing non-smokers with lung cancer is the widespread misconception that only smokers are at risk for this disease. This assumption often leads to a lack of awareness among both the public and healthcare providers, causing early symptoms—such as persistent cough, chest pain, or shortness of breath—to be overlooked or misattributed to benign conditions. As a result, non-smokers are frequently diagnosed at more advanced stages, when treatment options are limited and outcomes are poorer [American Cancer Society].

Research published in Lung Cancer journal underscores that delayed diagnosis is a common issue among non-smokers, who may not be considered for lung cancer screening or may face delays in diagnostic imaging and referral [Lung Cancer Journal]. This highlights the urgent need for increased education and awareness campaigns that target both patients and clinicians, emphasizing that lung cancer can affect anyone, regardless of smoking history. Improved public understanding and earlier consideration of lung cancer in symptomatic non-smokers could lead to timelier diagnoses and better survival rates.

41. Epigenetic Changes

Epigenetic changes refer to modifications in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence. These changes are increasingly recognized as important contributors to lung cancer risk, particularly in non-smokers. Environmental factors—such as air pollution, secondhand smoke, dietary habits, and chemical exposures—can cause epigenetic modifications like DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA interference. These processes can silence tumor suppressor genes or activate oncogenes, promoting the development and progression of cancer [National Cancer Institute].

Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic changes are potentially reversible, which opens new avenues for cancer prevention and therapy. Studies have shown that non-smokers with lung cancer often exhibit unique epigenetic signatures compared to smokers, reflecting differences in environmental exposures and biological pathways [NIH]. These findings underscore the importance of environmental stewardship and lifestyle choices in modifying cancer risk. Research into epigenetic therapies is ongoing, with the hope that targeting these reversible molecular changes could lead to more effective treatments for lung cancer, especially for those not driven by direct genetic mutations.

42. Inhaled Allergens

Chronic exposure to airborne allergens—such as pollen, pet dander, dust mites, and mold spores—may contribute to ongoing irritation and inflammation of the lung tissue, potentially elevating lung cancer risk in non-smokers. While inhaled allergens are most commonly associated with allergic conditions like asthma and allergic rhinitis, persistent inflammatory responses in the respiratory tract can lead to cellular damage and cycles of tissue repair, creating an environment conducive to genetic mutations and cancer development [NIH].

Studies have shown that chronic allergic inflammation can alter immune system function and disrupt normal cell signaling pathways in the lungs, which may contribute to carcinogenesis over time. For example, individuals with longstanding asthma or allergic bronchopulmonary diseases have been found to be at greater risk for lung cancer compared to the general population [Lung Cancer Journal]. Additionally, allergens can interact with other environmental pollutants, amplifying their harmful effects. Reducing exposure to inhaled allergens through improved indoor air quality, regular cleaning, and proper ventilation can help minimize chronic lung irritation and may play a role in lowering lung cancer risk for non-smokers.

43. Unregulated Building Materials

Exposure to unregulated or hazardous building materials, particularly asbestos, poses a significant risk for lung cancer in non-smokers. Asbestos was once widely used for insulation, fireproofing, and other construction purposes due to its durability and heat resistance. However, when asbestos-containing materials deteriorate or are disturbed during renovations, microscopic fibers can become airborne and inhaled, deeply embedding in lung tissue. Over time, these fibers cause chronic inflammation, scarring, and cellular damage, dramatically increasing the risk of lung cancer and mesothelioma [National Cancer Institute].

Despite strict regulations in many countries, asbestos remains present in older homes, schools, and workplaces, especially where building codes have not been updated or adequately enforced. Other unregulated materials, such as certain synthetic fibers, lead-based paints, or silica dust, may also contribute to lung cancer risk if inhaled over long periods [OSHA]. The continued presence of these hazardous substances underscores the importance of professional assessment and remediation during building renovations or demolitions. Raising awareness and enforcing strict safety standards are essential steps in protecting non-smokers from the hidden dangers of outdated or unregulated construction materials.

44. Use of Certain Cleaning Products

Regular use of certain cleaning products and solvents can expose non-smokers to airborne chemicals that may be harmful to lung tissue over time. Many household and industrial cleaners contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs), ammonia, bleach, and other reactive agents that can be easily inhaled, especially when used as sprays or in poorly ventilated spaces. Chronic exposure to these substances has been linked to respiratory irritation, inflammation, and oxidative stress, all of which can contribute to cellular damage and increase the risk of lung cancer [NIH].

A study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine found that long-term exposure to cleaning sprays and disinfectants was associated with a significant decline in lung function among professional cleaners and frequent household users [AJRCCM]. Some chemicals, such as formaldehyde and certain glycol ethers, are recognized carcinogens and can linger in the indoor environment. Using less toxic products, ensuring proper ventilation during cleaning, and wearing protective gear can help reduce harmful exposures. Increased awareness of these risks supports safer cleaning practices and long-term lung health for non-smokers.

45. Microplastic Inhalation

Microplastics—tiny fragments of plastic less than 5 millimeters in diameter—are increasingly recognized as ubiquitous environmental pollutants. Recent studies have revealed that microplastics can become airborne and are routinely inhaled by individuals in both indoor and outdoor environments. Sources include the breakdown of synthetic textiles, plastic packaging, and industrial processes. Once inhaled, these microscopic particles can penetrate deep into the lungs, where they may remain lodged in tissue and trigger chronic inflammation or immune responses [NIH].

Emerging evidence suggests that long-term exposure to inhaled microplastics could have detrimental effects on lung health. Animal studies and in vitro experiments have indicated that microplastics may cause oxidative stress, disrupt normal cell function, and even contribute to carcinogenesis by delivering toxic chemicals adsorbed on their surfaces [Nature]. Although human data is still limited, the potential for these particles to accumulate and cause harm is a growing concern, particularly in urban settings with high plastic use. Ongoing research is needed to fully understand the health implications of microplastic inhalation and to develop strategies for reducing exposure and protecting lung health in non-smokers.

46. Early Menopause

Emerging research has identified a link between early menopause—typically defined as the cessation of menstruation before age 45—and an increased risk of lung cancer in women who have never smoked. The underlying mechanism is believed to be related to significant hormonal shifts, particularly a reduction in estrogen levels. Estrogen has complex effects on lung tissue, influencing cellular growth, immune response, and DNA repair. An abrupt decline in estrogen may disrupt these protective mechanisms, making the lungs more susceptible to carcinogenic damage [National Cancer Institute].

A large prospective study published in The Lancet Oncology found that women who experienced early menopause had a higher incidence of lung cancer compared to those who underwent menopause at a typical age, even after adjusting for other risk factors [The Lancet Oncology]. These findings suggest a need for heightened lung health awareness and potentially earlier screening among women with early menopause, regardless of smoking history. Further research is ongoing to clarify the precise biological pathways involved and to determine whether hormone replacement therapy or other interventions might modify this risk.

47. Water Pipe (Hookah) Use

Water pipe, or hookah, smoking is often perceived as a safer alternative to cigarettes, but growing evidence indicates that it poses significant health risks—including an increased risk of lung cancer for non-cigarette smokers. Hookah smoke contains many of the same harmful substances found in cigarette smoke, such as nicotine, tar, heavy metals, and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. During a typical hookah session, users may inhale larger volumes of smoke over a longer period, resulting in even greater exposure to these toxic compounds [CDC].

Social hookah use is especially popular among young adults and in group settings, sometimes including individuals who do not otherwise smoke. Studies have demonstrated that both direct users and those exposed to secondhand hookah smoke can experience elevated levels of carcinogens in their bodies [American Cancer Society]. The charcoal used to heat hookah tobacco further contributes dangerous carbon monoxide and heavy metals. Despite misconceptions, hookah use is not risk-free and may contribute to lung cancer among non-smokers. Public health campaigns and education are needed to address these risks and dispel myths about the safety of water pipe smoking.

48. Persistent Cough or Hoarseness

A persistent cough or hoarseness is often dismissed as a minor respiratory issue, but these symptoms can sometimes be early warning signs of lung cancer—even in individuals who have never smoked. Chronic cough lasting more than three weeks, unexplained hoarseness, or changes in voice quality should not be ignored, as they may indicate underlying abnormalities in the lungs or airways. Studies have shown that non-smokers are more likely to delay seeking medical attention for these symptoms due to the misconception that lung cancer only affects smokers [American Cancer Society].

Medical guidelines recommend prompt evaluation of persistent respiratory symptoms, including physical examination, imaging (such as chest X-ray or CT scan), and referral to a specialist when necessary. Early detection of lung cancer dramatically improves treatment options and outcomes, regardless of smoking history [American Lung Association]. Raising awareness about the importance of timely investigation for chronic cough or hoarseness among both the public and healthcare providers is essential for reducing delayed diagnoses and improving survival rates in non-smokers with lung cancer.

49. Advances in Screening for Non-Smokers

With the rising incidence of lung cancer among non-smokers, there is increasing interest in refining screening guidelines and developing tools tailored to individuals without a history of tobacco use. Traditionally, lung cancer screening has focused on current and former heavy smokers, but new evidence suggests that certain high-risk non-smokers, such as those with a strong family history, exposure to radon or occupational hazards, or specific genetic mutations, could also benefit from regular screening [National Cancer Institute].

Low-dose computed tomography (CT) scans have emerged as a valuable tool for early detection, capable of identifying lung cancers at a stage when they are more treatable. Recent research is exploring personalized risk models that incorporate environmental, occupational, and genetic factors to identify non-smokers who might benefit from routine screening [American Lung Association]. Ongoing studies aim to further refine these models and reduce false positives, making screening safer and more effective. As awareness grows, expanded screening guidelines may help detect lung cancer earlier in high-risk non-smoking populations, ultimately improving survival rates and outcomes.

50. The Importance of Research and Awareness

The increasing incidence of lung cancer among non-smokers underscores the urgent need for ongoing research and robust public health awareness campaigns. Scientists are actively investigating a wide range of potential causes, from genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures to hormonal and lifestyle factors, in order to develop better prevention, screening, and treatment strategies. Large-scale studies, such as those supported by the National Cancer Institute and international collaborations, are critical for unraveling complex risk factors and improving risk assessment models for non-smokers [National Cancer Institute].

Public health organizations are also working to dispel the myth that lung cancer is solely a smoker’s disease. Awareness campaigns, such as the American Lung Association’s “Saved By The Scan,” encourage vigilance and promote early detection for all at-risk individuals, regardless of smoking status [American Lung Association]. By broadening public and clinical understanding, these efforts help ensure that persistent symptoms are not overlooked and that high-risk non-smokers receive timely medical attention. Continued investment in research, education, and advocacy is essential for reducing the burden of lung cancer and saving lives.

Conclusion

The rising rates of lung cancer among non-smokers highlight a critical public health challenge that demands urgent attention and continued investigation. Understanding the complex mix of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors is essential for effective prevention and early detection. Awareness of persistent respiratory symptoms, regular screening for those at risk, and staying informed about the latest scientific research can significantly improve outcomes [National Cancer Institute]. As new discoveries emerge, both individuals and healthcare providers must remain vigilant and proactive. Empowering the public with knowledge and access to care is key to combating lung cancer in non-smokers and saving lives in the years ahead.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational purposes only. While we strive to keep the information up-to-date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability with respect to the article or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained in the article for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this article.

Through this article you are able to link to other websites which are not under our control. We have no control over the nature, content, and availability of those sites. The inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them.

Every effort is made to keep the article up and running smoothly. However, we take no responsibility for, and will not be liable for, the article being temporarily unavailable due to technical issues beyond our control.