Early Behavioral Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease

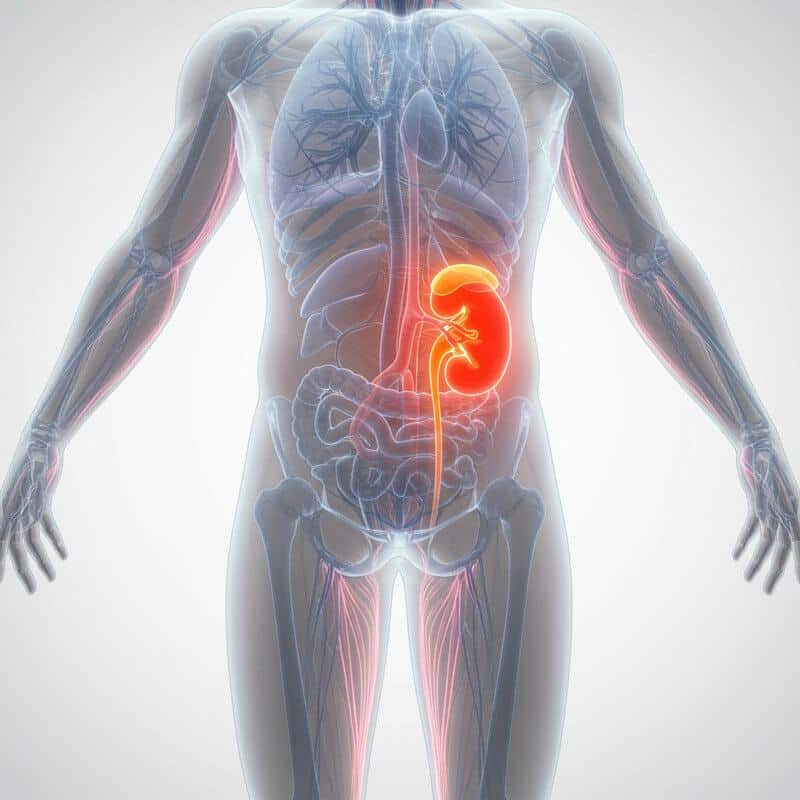

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common cause of dementia, affects over 6.7 million Americans in 2023, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. This progressive neurodegenerative disorder primarily targets the brain, gradually impairing memory, reasoning, and daily function. Early detection remains a significant challenge, as symptoms often go unnoticed until substantial cognitive decline occurs. Recognizing and understanding subtle behavioral changes in the initial stages is crucial for timely intervention and improved prognosis. This article explores those early behavioral indicators, aiming to foster awareness and facilitate prompt diagnosis.

1. Subtle Memory Lapses

One of the earliest and most recognizable behavioral changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease involves subtle lapses in short-term memory. Individuals may begin to forget recently learned information, misplace everyday items like keys or glasses, or struggle to recall appointments and conversations. For example, a person might repeatedly ask the same question or tell the same story within a short period, not realizing they have already done so. While occasional forgetfulness is a normal part of aging, consistent patterns of memory loss that interfere with daily life can signal the onset of Alzheimer’s.

It’s important to distinguish between common age-related forgetfulness and more persistent memory issues. If memory lapses become frequent, disrupt work or social activities, or are noticed by friends and family, it is advisable to seek professional evaluation. Early intervention can provide access to treatments and support that may slow the progression of symptoms. The National Institute on Aging recommends consulting a healthcare provider if memory problems are concerning or worsening, as they can help determine the underlying cause and recommend appropriate next steps.

2. Difficulty Finding Words

Changes in language processing often emerge early in Alzheimer’s disease, making it harder for individuals to find the right words during conversations. This symptom, known as aphasia, might manifest as pausing frequently, substituting incorrect words, or struggling to name familiar objects. For example, someone may refer to a “watch” as a “hand clock” or describe a “television” as “that thing you watch shows on.” These difficulties can lead to frustration and self-consciousness, prompting the individual to withdraw from social interactions.

Occasional word-finding difficulty happens to everyone, but Alzheimer’s-related changes are more persistent and noticeable. Caregivers and loved ones may observe that the person often trails off mid-sentence, repeats themselves, or relies on vague descriptions instead of specific terms. If such issues occur regularly and interfere with effective communication, it may be a sign of early cognitive decline. Experts at the Mayo Clinic recommend keeping a journal of language difficulties, which can help healthcare professionals assess patterns and provide an accurate diagnosis. Early recognition is key to accessing supportive therapies and interventions.

3. Repeating Questions or Stories

One of the hallmark behavioral indicators of early Alzheimer’s disease is the tendency to repeat questions or stories within short intervals. This repetitive speech is rooted in the disruption of memory formation and retrieval processes in the brain, specifically affecting the hippocampus and related structures responsible for short-term memory. As a result, individuals may not remember having asked a question or shared a story moments earlier and will unwittingly repeat themselves, often multiple times in the same conversation.

While it is common for older adults to occasionally repeat themselves, especially when distracted or tired, the frequency and context of repetition in Alzheimer’s is notably different. Repetitive questions or stories in Alzheimer’s occur much more often and are typically unprompted or unrelated to a recent discussion. For example, a loved one might ask, “What time is dinner?” several times in an hour, even after being answered. Caregivers should pay attention to how often this happens and in what situations. Keeping a record of these occurrences can help distinguish normal aging from potential cognitive decline. The Alzheimer’s.gov website offers guidance on observing and tracking these behavioral changes for timely intervention.

4. Misplacing Everyday Items

Another early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease is frequently misplacing everyday items, such as keys, wallets, glasses, or television remotes. This symptom is rooted in disruptions to spatial memory—the brain’s ability to remember where objects are located in one’s environment. People in the early stages of Alzheimer’s may put items in unusual places, like leaving the car keys in the refrigerator or placing a phone in a kitchen cabinet, and then struggle to retrace their steps to find them.

While everyone occasionally forgets where they left something, Alzheimer’s-related misplacement tends to be more pervasive and patterned. The difference lies in frequency and the inability to recall or logically deduce where the items might be. Individuals may accuse others of stealing or hiding their belongings when they cannot find them, further indicating a deeper cognitive disruption. Family members should take note if misplacing items becomes a frequent occurrence and is coupled with confusion about familiar environments. Distinguishing these patterns from normal forgetfulness is key to early recognition. The NHS offers more information on how spatial memory changes can signify the onset of Alzheimer’s and when to seek professional advice.

5. Withdrawal from Social Activities

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, individuals may begin to withdraw from social activities, hobbies, or group events they previously enjoyed. This withdrawal often stems from a growing awareness of cognitive difficulties, such as trouble following conversations, remembering names, or keeping up with the flow of group interactions. Embarrassment, frustration, or fear of making mistakes can further prompt people to isolate themselves, avoiding situations where their symptoms might become apparent to others.

It is important to distinguish this kind of withdrawal from depression, which can also cause loss of interest in socializing but is typically accompanied by persistent sadness, feelings of hopelessness, or changes in sleep and appetite. In Alzheimer’s, the withdrawal is often more situational—triggered by cognitive challenges rather than mood alone. Encouraging gentle, supportive social engagement tailored to the individual’s comfort and abilities can help maintain mental and emotional health. The Alzheimer’s Society recommends involving loved ones in familiar, low-pressure settings and monitoring for changes in participation. If social withdrawal persists or worsens, seeking professional advice can help determine whether Alzheimer’s or another condition may be responsible.

6. Mood Changes and Irritability

Early Alzheimer’s disease can trigger pronounced mood changes and increased irritability, often rooted in neurochemical shifts within the brain. As neurons degenerate and neurotransmitter levels—such as serotonin and acetylcholine—alter, individuals may experience unexpected emotional fluctuations. These neurochemical disruptions can make people more prone to anxiety, frustration, or even anger in situations they previously managed calmly.

Observable examples include becoming unusually upset over minor inconveniences, displaying impatience during routine activities, or reacting with anger to gentle corrections or reminders. Some individuals may seem more easily startled or overwhelmed by normal daily stimuli, resulting in sudden outbursts or withdrawal. Family and caregivers might notice a loved one becoming uncharacteristically suspicious, defensive, or quick to take offense. Such behaviors can be especially noticeable if the person was previously easygoing or emotionally stable.

It is essential to track new or worsening patterns of irritability, as these changes may signal the onset of Alzheimer’s as opposed to normal aging or life stressors. The National Institute on Aging recommends documenting mood swings and discussing them with a healthcare provider, since early intervention can help manage symptoms and improve coping strategies for both individuals and their caregivers.

7. Poor Judgment and Decision-Making

Impaired judgment and decision-making are common early behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease, often resulting from damage to the brain’s frontal lobes, which govern reasoning, planning, and impulse control. As Alzheimer’s progresses, individuals may struggle to assess risks or foresee the consequences of their actions. This can manifest in various ways, such as making uncharacteristically poor financial decisions—like giving away large sums of money, falling for telemarketing scams, or neglecting to pay bills on time.

Safety decisions may also be affected; a person might leave the stove on, wander outside inappropriately dressed for the weather, or disregard traffic rules while driving. These behaviors are typically out of character and represent a significant shift from previous patterns of responsible decision-making. Loved ones and caregivers should be alert to recurring risky or impulsive choices, especially if they involve money, personal safety, or the well-being of others.

Monitoring these changes is crucial, as poor judgment is often more severe and frequent than what is seen in normal aging. The Alzheimer’s Association emphasizes the importance of recognizing and addressing these warning signs early, as timely intervention can help protect the individual’s assets, safety, and independence for as long as possible.

8. Reduced Interest in Hobbies

A noticeable reduction in interest or participation in previously enjoyed hobbies is a frequent early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease. This decline in initiative is believed to be related to altered brain function, including changes in motivation and reward pathways. Individuals might lose enthusiasm for activities such as gardening, crafting, playing music, or participating in clubs or sports, even if these activities once brought them great joy or were a regular part of their routine.

For example, someone who loved painting may leave projects unfinished or stop creating art altogether, or a passionate reader might lose interest in books and magazines. This apathy is distinct from occasional boredom or shifting interests that are normal with aging. In Alzheimer’s, the loss of initiative is persistent and often extends across multiple areas of life. Caregivers and family members should pay attention to changes in participation, declining attendance at favorite events, or a lack of excitement about upcoming activities.

Tracking these changes can help differentiate between Alzheimer’s-related apathy and other causes, such as depression. The Alzheimer’s Society provides additional information on how a reduction in initiative can signal cognitive decline and when to seek professional advice.

9. Trouble Following Conversations

Difficulty following conversations is a subtle but significant early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, often resulting from cognitive processing delays. As the brain’s ability to process and retain information diminishes, individuals may struggle to keep up with discussions, particularly in group settings where multiple people are speaking or the topic shifts rapidly. They might lose track of what is being said, miss key points, or become confused about who is speaking. This can lead to feelings of frustration, embarrassment, or withdrawal from social situations.

In real-life scenarios, someone experiencing these changes may frequently ask others to repeat themselves, respond inappropriately, or appear disengaged during conversations. For example, at a family dinner or community meeting, they might lose their place in the discussion or have trouble remembering comments made just moments earlier. Such difficulties go beyond occasional lapses in attention or normal age-related changes in hearing or concentration.

It is important to monitor for recurring confusion or signs that someone is struggling to understand or follow along in conversations. The National Institute on Aging advises that consistent problems with conversation tracking may indicate early cognitive decline and warrant evaluation by a healthcare professional.

10. Changes in Sleep Patterns

Alterations in sleep patterns are frequently observed in individuals with early Alzheimer’s disease, largely due to disruptions in the brain’s circadian rhythms. The disease can interfere with the body’s internal clock, leading to difficulty falling asleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, or increased daytime sleepiness. Some people may begin to wander or become restless during the night, a symptom known as “sundowning,” which can be particularly distressing for both the individual and caregivers.

While it is normal for sleep patterns to change somewhat with age—such as needing less sleep or waking up earlier—Alzheimer’s-related sleep disturbances are often more severe and persistent. Unlike typical aging, these changes may appear suddenly and cause significant daytime impairment, irritability, or confusion. Caregivers may notice that their loved one naps excessively during the day or experiences reversed sleep-wake cycles.

It is important to consult a healthcare provider if sleep disruptions become frequent, interfere with daily functioning, or are accompanied by other cognitive changes. The Alzheimer’s Association offers information on sleep issues and strategies for managing them. Early intervention can help identify underlying causes and provide guidance for improving sleep quality and overall well-being.

11. Increased Anxiety

Early Alzheimer’s disease can lead to heightened anxiety, which often stems from neurological changes in the brain. As the disease disrupts neural circuits involved in regulating emotion and processing new information, individuals may become increasingly anxious, especially in unfamiliar or challenging situations. This anxiety may be triggered by confusion, difficulties with memory, or an increasing awareness of cognitive limitations.

Situational examples include heightened worry when routines are disrupted, becoming fearful or agitated in crowded or noisy environments, or expressing excessive concern about personal safety or the whereabouts of loved ones. Someone might repeatedly ask if the doors are locked, become distressed when plans change, or express new anxieties about being left alone. These symptoms can be especially pronounced in the evening or when the individual is tired or overstimulated.

It is important to track new or worsening anxiety symptoms, as persistent anxiety can impact quality of life and signal the progression of Alzheimer’s. Caregivers and family members should note changes in behavior and discuss them with a healthcare provider. The Alzheimer’s Association provides resources for managing anxiety and guidance on when to seek professional help for ongoing or severe symptoms.

12. Unusual Suspicion or Paranoia

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, some individuals may develop unusual suspicion or paranoia, often in response to memory lapses and confusion. As the ability to remember where items were placed or to recall recent events diminishes, a person might begin to believe that others are stealing from them, hiding their possessions, or plotting against them. These beliefs are not rooted in reality but instead arise as the brain struggles to make sense of missing memories or misplaced objects.

Common examples include accusing family members or caregivers of theft when items like keys, wallets, or important documents are lost, or suspecting that someone is tampering with personal belongings. In some cases, individuals may become wary of neighbors, friends, or even long-trusted loved ones without reasonable cause. Such suspicions can lead to strained relationships, increased isolation, and heightened anxiety or distress.

If unusual suspicion or paranoia becomes persistent or begins to interfere with daily life, it is important to seek professional guidance. According to the National Institute on Aging, early intervention can help manage these symptoms, provide support for families, and distinguish between Alzheimer’s-related paranoia and other possible causes, such as psychiatric conditions or medication side effects.

13. Difficulty Adapting to Change

One of the early behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease is a marked difficulty adapting to changes in routine or environment. This inflexibility arises from the brain’s declining ability to process new information, adjust to unfamiliar situations, and manage stress. Even minor disruptions, such as a change in daily schedule, moving furniture, or visiting new places, can trigger confusion, anxiety, or agitation.

While it is normal for people of any age to prefer familiar routines, the resistance seen in early Alzheimer’s is often extreme and can be disproportionate to the situation. For example, a person who once enjoyed spontaneity may become distressed by an unexpected visitor or a slight shift in meal time. They may insist on performing tasks in a particular way or refuse to participate in activities that deviate from their routine, even if those changes are minor or beneficial.

Practical warning signs include repeated complaints about changes, visible distress in unfamiliar settings, or withdrawal from activities involving unpredictability. Caregivers should observe for an increasing rigidity in habits and a heightened sense of unease when routines are altered. The Alzheimer’s Society offers tips on supporting loved ones through transitions and when to consider professional advice if adaptation becomes a persistent struggle.

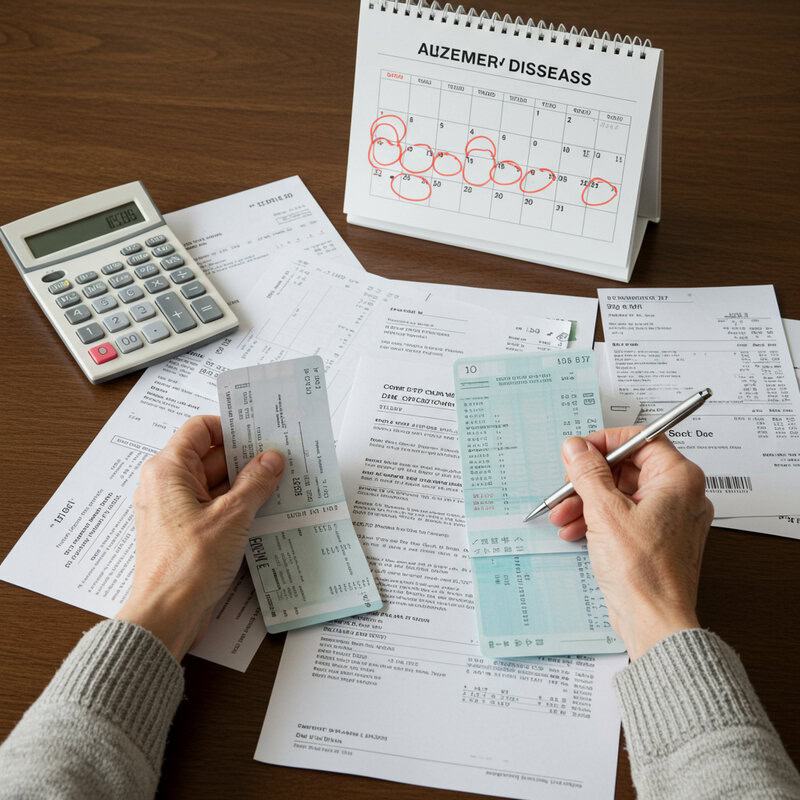

14. Problems Managing Finances

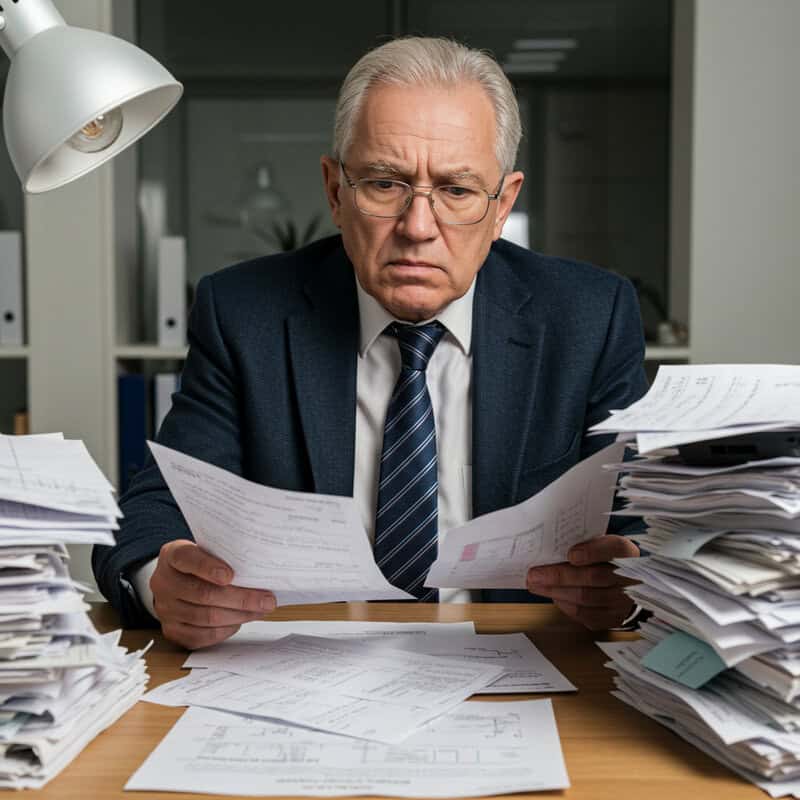

Difficulty managing finances is an early and telling behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, often stemming from impairment in executive function. Executive function refers to the brain’s ability to plan, organize, and carry out complex tasks—skills essential for handling money, budgeting, and paying bills. As Alzheimer’s progresses, individuals may find it increasingly challenging to keep track of due dates, balance checkbooks, or understand bank statements.

For example, someone who previously managed household finances with ease may begin to miss bill payments, make repeated or erroneous payments, or struggle to follow multi-step instructions for online banking. They might forget to deposit checks, neglect to pay utilities, or fall victim to scams due to poor judgment. These financial errors are often more frequent and severe than the occasional mistake seen with normal aging.

Family members and caregivers should be alert for signs such as unopened mail, bounced checks, or increased anxiety about money matters. Monitoring bank statements and financial correspondence can help catch problems early. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau offers resources on protecting older adults from financial mishaps and fraud, and suggests seeking professional help if financial management becomes problematic.

15. Decline in Personal Hygiene

A decline in personal hygiene is a common early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease and is often the result of both apathy and forgetfulness. As the disease affects regions of the brain responsible for motivation and memory, individuals may lose the initiative to maintain regular self-care routines or simply forget important tasks such as bathing, brushing teeth, changing clothes, or combing hair. This decline can appear suddenly in someone who previously took pride in their appearance and grooming.

While poor hygiene can also be a symptom of depression, the causes and presentation differ. In depression, a lack of self-care is typically coupled with persistent sadness, hopelessness, and withdrawal from most activities. In contrast, Alzheimer’s-related decline in hygiene often occurs without pronounced mood changes and may be accompanied by confusion about the process or sequence of daily grooming tasks.

It is important for caregivers and loved ones to monitor changes in grooming habits, such as wearing the same clothes repeatedly, neglecting to shave, or skipping showers. The Alzheimer’s Association provides guidance on supporting personal care needs and recommends seeking professional advice if declines in hygiene become evident or persistent, as early intervention can improve quality of life.

16. Getting Lost in Familiar Places

One of the more alarming early behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease is an increased tendency to get lost or disoriented in familiar places. This symptom arises from a decline in spatial navigation, a cognitive function that allows individuals to understand and remember their environment and how to move through it. As Alzheimer’s affects the areas of the brain responsible for spatial memory, even routine outings—such as neighborhood walks, grocery shopping, or visiting a friend’s house—can become confusing and overwhelming.

For example, a person who has walked the same route to the local store for years may suddenly lose their way, take wrong turns, or forget their purpose mid-walk. They may have difficulty finding their way home, even from places very close by. This level of disorientation is far beyond typical age-related forgetfulness and can pose significant safety risks.

It is crucial to intervene if a loved one begins to exhibit signs of getting lost in familiar environments. Caregivers should take preventive measures such as accompanying the person on outings and using identification jewelry. The Alzheimer’s Association provides practical advice on managing wandering and when to seek professional help, emphasizing the importance of safety and early intervention.

17. Disorganization at Home

Disorganization at home is a subtle yet telling early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, often reflecting problems with planning, sequencing, and organizational skills. As Alzheimer’s begins to affect the brain’s frontal lobes, individuals may struggle to keep track of household tasks, maintain routines, or put items away in their proper places. This decline can lead to increasing clutter, misplaced belongings, or neglected chores.

Common signs include stacks of unopened mail, dishes piling up, laundry left unfinished, or items such as kitchen utensils being found in odd locations. The home may become noticeably messier, with once-orderly spaces devolving into disarray. This level of disorganization is typically more pronounced than occasional untidiness and may make daily living more challenging or even unsafe.

Practical monitoring involves observing changes in the person’s ability to manage home-related responsibilities, such as making grocery lists, following recipes, or keeping appointments. Loved ones should take note if clutter accumulates rapidly, bills go unpaid, or important documents are misplaced. The National Institute on Aging offers helpful resources for creating a safer, more manageable home environment and recognizing when disorganization may indicate early Alzheimer’s or another cognitive issue.

18. Requiring Repeated Reminders

Needing repeated reminders for daily tasks is a common early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, closely linked to short-term memory loss. As the brain’s ability to encode and retrieve recent information diminishes, individuals may forget to take medications, attend appointments, or complete household chores—even after just being reminded. For example, someone may repeatedly ask, “What time is my doctor’s appointment?” or “Did I already take my pills today?” within a short span of time.

While it is normal for older adults to occasionally need reminders—especially during times of stress or busyness—Alzheimer’s-related memory lapses are more pervasive and persistent. The difference lies in the frequency and necessity: reminders become a constant part of daily life, and even written notes or alarms may not suffice. This can lead to missed obligations, confusion, and frustration for both the individual and their caregivers.

If someone begins to rely heavily on repeated prompts for basic routines or seems unable to retain new information, it is important to consider a professional evaluation. The National Institute on Aging recommends seeking guidance if reminders become essential for everyday functioning, as this may indicate the onset of Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia.

19. Difficulty Planning or Organizing

Difficulty with planning or organizing is a key early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, resulting from executive dysfunction. Executive functions are high-level cognitive processes that allow individuals to set goals, develop strategies, and sequence steps to achieve desired outcomes. When these processes are impaired, even routine activities can become confusing and overwhelming.

For instance, meal preparation—a task that requires deciding what to cook, gathering ingredients, following a recipe, and timing each step—can suddenly become challenging. A person might forget necessary items, mix up the order of steps, or abandon the process altogether. This difficulty extends beyond the kitchen to other aspects of life, such as managing appointments, handling correspondence, or organizing social outings.

While occasional disorganization is common with age, especially during stressful periods, persistent trouble organizing daily tasks may signal early Alzheimer’s. Family and caregivers should watch for signs such as missed appointments, incomplete projects, or confusion about how to start or finish multi-step activities. The Alzheimer’s Association highlights these organizational challenges as important warning signs and encourages seeking a professional assessment if they become frequent or interfere with independence.

20. Loss of Empathy

Loss of empathy is an early behavioral symptom sometimes observed in Alzheimer’s disease, caused by changes in the brain’s regions responsible for emotional processing and social awareness, such as the frontal and temporal lobes. As these areas become affected, individuals may find it increasingly difficult to recognize or respond to the feelings of others, leading to a noticeable decline in warmth, sensitivity, and compassion during social interactions.

For example, a person who once comforted friends in distress or celebrated family milestones with enthusiasm may now appear indifferent or unresponsive. They might not notice when someone is upset, fail to offer support, or react inappropriately to another’s emotions. This shift can be particularly distressing for loved ones, who may feel hurt or confused by the sudden lack of emotional connection.

It’s important to differentiate this loss of empathy from personality changes associated with mood disorders or stress. If a previously caring individual becomes unusually detached or indifferent to others’ feelings, it could be an early sign of Alzheimer’s-related cognitive decline. The National Institutes of Health provides further insight into the social and emotional changes linked to dementia and suggests seeking evaluation if empathy loss is observed.

21. Reduced Awareness of Time

Reduced awareness of time, or temporal disorientation, is a common early sign of Alzheimer’s disease. This symptom involves losing track of dates, seasons, or the passage of time, and may stem from degeneration of brain regions involved in processing temporal information. Unlike normal daydreaming or momentary distraction, which are brief and harmless, temporal disorientation in Alzheimer’s is persistent and can significantly disrupt daily routines.

For example, an individual may forget what day of the week it is, become confused about the time of day, or misjudge how much time has passed between events. They might dress inappropriately for the season or repeatedly ask about upcoming appointments, even after being informed. These difficulties can lead to missed obligations, confusion about meal times, or trouble adhering to medication schedules.

Confusing time occasionally is common, especially during periods of stress or fatigue. However, when time confusion becomes frequent and begins to interfere with daily functioning or causes distress, it may be indicative of early Alzheimer’s. The National Institute on Aging suggests seeking professional evaluation if reduced time awareness is observed, as early intervention can help manage risks and improve quality of life.

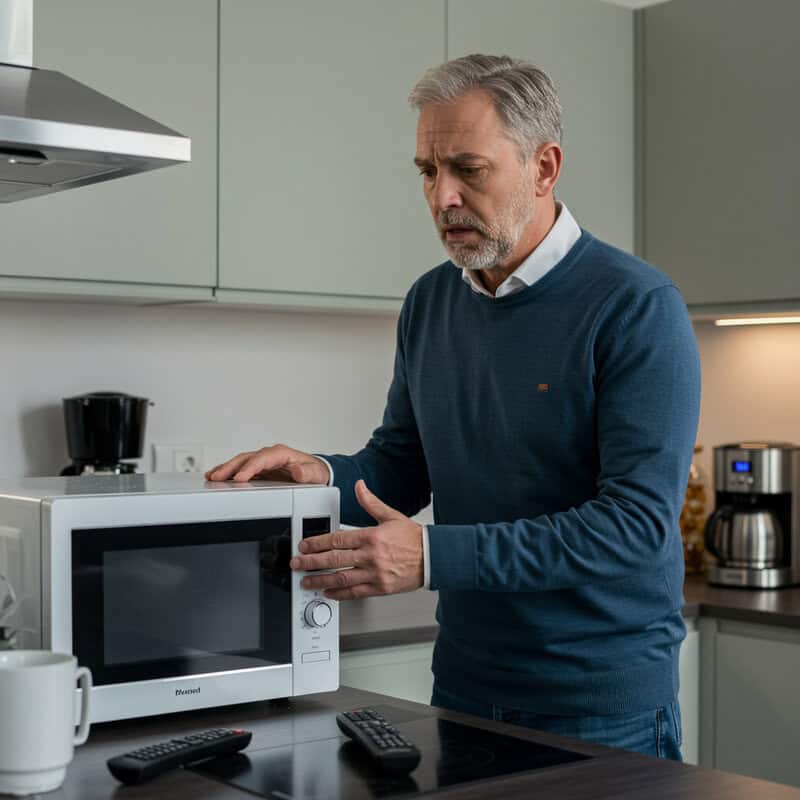

22. Struggling with Familiar Tasks

Struggling with familiar tasks, such as using household appliances or managing simple routines, is a prominent early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease. As the brain’s neural networks responsible for learned skills and procedural memory deteriorate, individuals may have trouble completing activities they once performed effortlessly. This can include difficulty operating a microwave, setting a television remote, or following the steps to brew coffee—despite years of experience with these tasks.

Unlike occasional lapses that everyone experiences, such as momentarily forgetting how to program a device, Alzheimer’s-related struggles are persistent and often escalate over time. A person may repeatedly ask for help with operating appliances, skip steps in a familiar recipe, or abandon tasks halfway through. These changes can jeopardize safety and undermine daily independence, making it harder for the individual to live on their own without support.

It’s important for caregivers and family members to note any decline in the ability to manage daily routines or self-care, as this may be an early indicator of cognitive impairment. The Alzheimer’s Association recommends monitoring these skills and seeking professional advice if difficulties with familiar tasks become noticeable or begin to interfere with everyday life.

23. Inappropriate Social Behavior

Inappropriate social behavior is a potential early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, often resulting from a loss of social inhibitions and changes in judgment. As the disease affects the brain’s frontal lobes—areas responsible for self-control and social awareness—individuals may struggle to interpret social cues or understand acceptable conduct in public settings. This can lead to actions that seem out of character or socially awkward.

Examples include making insensitive comments, interrupting others, invading personal space, or displaying a lack of tact in conversations. A person might laugh at inappropriate moments, speak loudly in quiet environments, or use language that is uncharacteristically blunt. In more pronounced cases, behaviors such as inappropriate touching, undressing in public, or disregarding social norms can occur, causing embarrassment or discomfort for both the individual and those around them.

These shifts are distinct from occasional lapses in etiquette, which can happen to anyone. In Alzheimer’s, inappropriate social behavior is often repetitive and marked by a noticeable change from previous manners or personality. The NHS advises monitoring for out-of-character actions and consulting with healthcare professionals if such behaviors emerge, as early intervention can help manage symptoms and maintain dignity.

24. Changes in Appetite or Eating Habits

Changes in appetite or eating habits are often seen in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, largely due to alterations in hypothalamic control and disruptions in the brain’s reward and recognition systems. The hypothalamus helps regulate hunger and satiety, and when affected by Alzheimer’s, individuals may experience significant shifts in their desire for food or eating routines. This can manifest as increased appetite, reduced interest in meals, or unusual cravings and eating patterns.

For example, someone who previously maintained a balanced diet may suddenly develop a strong preference for sweets, eat the same foods repetitively, or forget to eat altogether. Others might overeat, have difficulty recognizing when they are full, or lose interest in foods they once enjoyed. These changes can sometimes lead to weight loss, weight gain, or nutritional deficiencies.

It is important for caregivers and family members to monitor for abrupt or persistent dietary changes, as they may indicate the onset or progression of Alzheimer’s. Keeping a food diary and observing patterns can be helpful. The Alzheimer’s Association offers practical guidance on managing changes in appetite and ensuring nutritional needs are met throughout the course of the disease.

25. Increased Clumsiness or Falls

Increased clumsiness or a higher frequency of falls can be an early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, stemming from a gradual decline in motor coordination and spatial awareness. As the disease impacts the brain regions responsible for movement and balance, individuals may become less steady on their feet, have trouble judging distances, or misjudge the location of objects in their environment. This can lead to bumping into furniture, dropping items, or tripping over familiar obstacles.

Unlike conditions such as arthritis, which primarily affect the joints and cause pain-related mobility issues, motor problems in Alzheimer’s are related to cognitive and neurological decline. The clumsiness is often accompanied by confusion or disorientation, and may occur even in those who have no significant physical limitations.

It is important to note when falls or minor injuries become more frequent, as this can be a sign of worsening motor and cognitive function. Caregivers should monitor for bruises, unexplained injuries, or increased reports of stumbling. The National Institute on Aging provides resources on fall prevention and recommends seeking medical evaluation if motor changes lead to repeated falls or safety concerns.

26. Difficulty Interpreting Visual Information

Difficulty interpreting visual information is a notable early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, often stemming from visual-spatial processing deficits in the brain. As the disease affects the occipital and parietal lobes, individuals may have trouble distinguishing contrast, judging distances, or understanding spatial relationships between objects. This can make everyday tasks and navigation more challenging, even in well-known environments.

Real-life examples include misjudging the height of steps or curbs, knocking over glasses, or having trouble pouring liquids without spilling. Some people may struggle to interpret maps, recognize faces, or follow visual patterns, which can lead to confusion and frustration. Driving may become especially hazardous, as interpreting traffic signals, reading signs, or gauging the distance between vehicles becomes increasingly difficult.

Caregivers and loved ones should watch for signs of navigation trouble, such as hesitancy when moving through rooms, bumping into furniture, or avoiding unfamiliar places due to visual confusion. Persistent or worsening visual-spatial difficulties should prompt consideration of a professional evaluation. The Alzheimer’s Association highlights visual processing changes as a key warning sign and provides resources for adapting the environment to increase safety and support independence.

27. Fixation on Specific Ideas or Activities

Fixation on specific ideas or activities is a behavioral change commonly seen in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals may develop repetitive behaviors or become preoccupied with certain routines, topics, or concerns. This is believed to stem from neurological changes that reduce cognitive flexibility and the ability to shift focus or adapt to new situations. As a result, the person may ask the same question repeatedly, insist on performing daily rituals in a precise manner, or dwell excessively on minor worries.

Examples include repeatedly checking whether the door is locked, obsessively organizing personal items, or focusing conversation on a single subject regardless of context. These behaviors go beyond simple habit; they become rigid, and attempts to redirect the individual can result in anxiety or agitation. The fixation may also relate to a specific activity, such as watching the same television program multiple times a day or endlessly sorting papers.

While some routines are normal and even comforting, fixation in Alzheimer’s can disrupt daily life, interfere with social interactions, or prevent engagement in other important activities. The Alzheimer’s Society suggests monitoring for repetitive or obsessive behaviors and consulting a healthcare professional if these patterns become distressing or disruptive for the individual or their caregivers.

28. Unusual Emotional Outbursts

Unusual emotional outbursts are a frequent early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, stemming from impaired emotional regulation as the condition affects the brain’s frontal and limbic regions. Individuals may experience intense and unexpected expressions of emotion, such as sudden anger, frustration, or crying, often out of proportion to the situation or without an obvious trigger. This loss of control can be confusing and distressing for both the person with Alzheimer’s and those around them.

For example, someone might become inexplicably angry over a minor inconvenience, such as a misplaced item or a change in routine, or burst into tears during a benign conversation. These reactions may seem to occur without warning and may not align with the person’s previous temperament. Simple attempts at reassurance or redirection can sometimes escalate the emotional response, leaving caregivers feeling helpless or bewildered.

It is important to track the intensity, frequency, and potential triggers of these outbursts to provide helpful information to healthcare professionals. The Alzheimer’s Association offers strategies for managing emotional changes and emphasizes that persistent or severe outbursts should prompt further assessment to ensure proper support and intervention for both the individual and their caregivers.

29. Restlessness or Wandering

Restlessness and wandering are common early behaviors in Alzheimer’s disease, frequently resulting from disorientation, confusion, or a desire to find something familiar. Unlike the purposeful pacing seen in anxiety, wandering in Alzheimer’s often lacks clear intent and can occur at any time of day or night. Individuals may feel compelled to move around, leave the house, or roam their environment, sometimes expressing a need to “go home” even when they are already there.

This restlessness may manifest as aimless walking from room to room, standing up repeatedly, or attempting to leave the house without a specific destination. These behaviors are often triggered by boredom, discomfort, environmental changes, or a search for security. However, wandering poses significant safety risks, including exposure to the elements, getting lost, or encountering dangerous situations like traffic or unfamiliar areas.

Caregivers and loved ones should be vigilant if restlessness leads to attempts to leave safe environments or becomes increasingly frequent. The Alzheimer’s Association provides detailed guidance on preventing wandering and outlines strategies for ensuring the safety of those at risk, including using door alarms, identification bracelets, and structured routines to reduce the urge to wander.

30. Increased Sensitivity to Noise or Stimuli

Increased sensitivity to noise or other sensory stimuli is a frequently observed early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease. As the brain’s ability to process and filter sensory information becomes impaired, individuals may find everyday environments—such as busy restaurants, crowded shopping centers, or even family gatherings—overwhelming and distressing. Sounds that once went unnoticed, like the hum of appliances or the chatter of a group, can suddenly seem unbearably loud or confusing.

For example, a person may become agitated or anxious in noisy places, cover their ears, or ask to leave crowded rooms. They might react strongly to sudden sounds or bright lights, or seem distracted and unable to focus when multiple stimuli are present. This hypersensitivity can lead to withdrawal from social situations, frustration, or emotional outbursts.

Caregivers should note instances of overstimulation and any changes in tolerance for noise or activity levels. The Alzheimer’s Society recommends adapting the environment to minimize overwhelming stimuli and seeking professional advice if increased sensitivity interferes with daily life, as this symptom may indicate progression of Alzheimer’s or another cognitive disorder.

31. Trouble Recognizing Faces

Trouble recognizing faces, medically known as prosopagnosia or “face blindness,” can be an early behavioral sign of Alzheimer’s disease. As Alzheimer’s affects the brain regions responsible for visual recognition and memory, individuals may struggle to identify even close family members or friends, especially in group settings or when someone’s appearance changes slightly. This difficulty can be particularly noticeable at family gatherings or social events, where the person may hesitate, greet loved ones awkwardly, or mistake acquaintances for strangers.

Unlike occasional forgetfulness, such as taking a moment to recall a name, prosopagnosia in Alzheimer’s can be persistent and distressing. The individual might fail to recognize familiar faces despite repeated introductions, or require cues like voice, clothing, or context to identify people. This issue can extend beyond family to neighbors, caregivers, or even themselves when looking in a mirror.

Caregivers and family members should watch for confusion with acquaintances, repeated requests for introductions, or signs of anxiety in social situations. The National Institute on Aging offers guidance on recognizing visual and memory-related changes and suggests seeking professional evaluation if face recognition difficulties increasingly disrupt social interaction or emotional well-being.

32. Misunderstanding Sarcasm or Jokes

Misunderstanding sarcasm or jokes is a subtle but telling early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, often reflecting a decline in abstract thinking and the ability to interpret non-literal language. As the disease affects the brain regions responsible for processing complex social cues and nuanced communication, individuals may become more literal in their understanding. They might miss the intended humor or sarcasm behind a comment, take jokes at face value, or respond inappropriately to playful teasing.

For example, during a lighthearted conversation at dinner, someone with early Alzheimer’s may not recognize when a family member is joking and could become confused, offended, or simply not react at all. They may ask for clarification or seem puzzled by humor that once made them laugh. Over time, this decline can lead to awkward social exchanges and may contribute to withdrawal from group settings where banter or wordplay is common.

Caregivers and loved ones should monitor for noticeable changes in social comprehension, especially if the person was previously quick-witted or enjoyed humor. The Alzheimer’s Association emphasizes that difficulty understanding jokes, sarcasm, or figurative language is an important sign to discuss with a healthcare professional for further assessment.

33. Loss of Motivation at Work or Volunteering

Loss of motivation, or apathy, is a frequent early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and can have a significant impact on work or volunteer activities. As the disease affects the brain’s motivation and reward centers, individuals may lose interest in projects, stop pursuing professional goals, or struggle to initiate tasks they previously found meaningful. This diminished drive often results in declining job performance or reduced engagement in volunteer roles.

In the workplace, colleagues may notice that the individual is less enthusiastic about assignments, misses deadlines, or requires more reminders and supervision. They may withdraw from meetings, avoid new responsibilities, or show little interest in problem-solving and collaboration. In volunteer settings, someone may stop attending events, neglect commitments, or participate less actively than before. These changes in motivation are out of character and not explained by external stressors or life changes.

It’s important to monitor for ongoing drops in performance, attendance, or initiative, especially if these behaviors are unusual for the person. The National Institutes of Health provides evidence linking apathy and loss of motivation to early Alzheimer’s and suggests that persistent changes in work or volunteering habits warrant evaluation by a healthcare professional to identify underlying causes and provide support.

34. Difficulty with Technology

Difficulty with technology is an increasingly recognized early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, especially as digital devices become more integral to daily life. Individuals may struggle with routine technology tasks that were once second nature, such as checking email, texting, making phone calls, or using household appliances like microwaves and televisions. These challenges are often rooted in impaired memory, reduced problem-solving skills, and difficulty learning new processes.

For example, a person might repeatedly forget passwords, mix up steps when sending an email, or be unable to navigate familiar phone menus. Frustration may arise when trying to operate devices they previously used with ease, leading to frequent requests for help or avoidance of technology altogether. Unlike the normal learning curve with new gadgets, these struggles persist even with repeated instruction and are accompanied by a decline in overall independence.

Caregivers and family members should watch for mounting frustration, anxiety, or confusion when using technology. The Alzheimer’s Society recommends monitoring changes in the ability to manage devices, as difficulty with technology can be an early sign of cognitive decline and may signal the need for a professional assessment or additional support at home.

35. Over- or Under-Reaction to Situations

Over- or under-reaction to everyday situations is a notable early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting disruptions in the brain’s emotional regulation centers. Individuals may display disproportionate responses to minor events, such as becoming extremely upset over a small mistake or, conversely, showing little or no reaction to significant news or stressful circumstances. This alteration in emotional expression can be confusing both for the individual and those around them.

Practical examples include crying intensely after misplacing an item, becoming enraged over a minor disagreement, or showing indifference to events that would normally elicit strong feelings, such as a family celebration or a friend’s illness. In some cases, a person may laugh inappropriately during serious conversations or seem emotionally flat when others are visibly affected by a situation. These reactions differ from normal personality quirks or mood variations, as the responses are consistently out of proportion or contextually inappropriate.

Caregivers and loved ones should pay attention to patterns of exaggerated or diminished emotional responses, as these may indicate early cognitive or neurological changes. The National Institute on Aging recommends documenting such behaviors and discussing them with a healthcare professional, as early recognition can guide appropriate support and intervention.

36. Loss of Direction or Purpose

Loss of direction or purpose is a subtle yet significant early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, manifesting as confusion about goals, plans, or the next steps in daily routines. Individuals may struggle to recall what they intended to do, lose track of personal objectives, or find it difficult to initiate or complete tasks. This confusion can lead to a sense of aimlessness, with the person appearing disengaged or wandering through their day without clear motivation.

For example, someone might forget the reason for entering a room, miss scheduled appointments, or abandon projects they started only moments before. They may repeatedly ask what they were supposed to be doing or express uncertainty about the day’s plans. Over time, this loss of direction can affect self-esteem and lead to withdrawal from previously enjoyed activities or responsibilities.

Caregivers and family members should take note if a loved one exhibits new or increasing signs of aimlessness, such as frequent unfinished tasks, missed appointments, or difficulty setting and following through with goals. The National Institute on Aging recommends discussing these changes with a healthcare professional, as early recognition and intervention can help manage symptoms and support continued engagement in meaningful activities.

37. Difficulty Understanding Instructions

Difficulty understanding instructions is a common early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting a decline in comprehension and the ability to process complex information. As the condition affects areas of the brain involved in language and reasoning, individuals may struggle to follow multi-step directions or grasp the details of verbal or written instructions. This can become evident during everyday tasks, such as attempting to follow a recipe, assemble an item, or carry out instructions from a doctor or family member.

For instance, a person may become confused when asked to perform a sequence of actions, skip steps when baking, or repeatedly ask for clarification when given directions. These comprehension issues are more persistent and pronounced than the occasional misunderstandings everyone experiences, and they can lead to frustration, incomplete tasks, or avoidance of activities that once felt manageable.

Caregivers and loved ones should pay attention if confusion about instructions becomes a recurring theme, especially if the individual was previously independent in managing such tasks. The Alzheimer’s Society advises seeking professional guidance if persistent difficulty understanding instructions interferes with daily life, as early intervention may help maintain independence and confidence.

38. Sudden Shifts in Political or Religious Beliefs

Sudden and uncharacteristic shifts in political or religious beliefs can be an early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting deeper personality changes and alterations in core values. As the disease impacts brain regions responsible for judgment, self-identity, and emotional stability, individuals may abruptly adopt views that contrast sharply with lifelong beliefs. These changes often appear in family discussions or group settings, where the individual might express opinions or support causes that are inconsistent with their previous convictions.

For example, a person who was once deeply involved in a particular faith tradition may suddenly lose interest or criticize practices they previously embraced. Similarly, someone with longstanding political affiliations may switch allegiances or advocate for positions they previously opposed, sometimes with little explanation or apparent understanding of the issues. These reversals can be distressing for family and friends, particularly when they are accompanied by other cognitive or behavioral changes.

Caregivers and loved ones should watch for abrupt, unexplained changes in expressed values or beliefs, especially when these are not aligned with major life events or external influences. The National Institutes of Health highlights that shifts in values and personality can be a marker of early Alzheimer’s, warranting professional evaluation and supportive conversation.

39. Neglecting Mail or Important Messages

Neglecting mail or important messages is a frequent early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, often resulting from diminished attention, prioritization, and organizational skills. As cognitive decline affects the ability to focus and recognize what needs immediate action, individuals may leave mail unopened, overlook bills, or ignore messages from friends, family, or service providers. Over time, this neglect can create practical problems—such as missed payments, service disruptions, or unaddressed personal matters.

For example, stacks of unopened envelopes may accumulate on the kitchen table, urgent notes may be misplaced or forgotten, and voicemails or texts may go unanswered. This pattern is distinct from the occasional oversight seen in busy or stressful times, as it tends to be persistent and progressively worsens, ultimately interfering with daily functioning and financial stability.

Caregivers and loved ones should watch for signs that important communications are being consistently overlooked, leading to late fees, missed appointments, or confusion about ongoing obligations. The National Institute on Aging recommends monitoring these behaviors and seeking professional guidance if neglect of mail or messages becomes a pattern, as this may indicate the need for additional support or intervention.

40. Unfounded Fears or Phobias

Unfounded fears or phobias can emerge as an early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, stemming from alterations in the brain’s fear circuits, including areas like the amygdala and hippocampus. These changes can distort the way individuals perceive threats or safety, leading to new and irrational anxieties about situations or objects that never caused concern before. The fears may seem unreasonable to family and friends, yet feel very real and distressing to the individual experiencing them.

Examples include suddenly being afraid to leave the house, expressing intense fear of household appliances, distrusting familiar people, or worrying excessively about being alone or about unlikely dangers such as burglars or accidents. These anxieties can result in avoidance behaviors, withdrawal from activities, or resistance to necessary routines, such as bathing or medical appointments.

It is important for caregivers and loved ones to monitor for the appearance of new or escalating fears, especially if they interfere with daily life or cause significant distress. The Alzheimer’s Association recommends discussing persistent or severe anxieties with a healthcare professional, as these symptoms may signal progression of Alzheimer’s and may benefit from targeted support or intervention.

41. Loss of Sense of Humor

Loss of sense of humor is a subtle but meaningful early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting alterations in emotional appreciation and social engagement. As the brain’s ability to interpret and respond to humor diminishes, individuals may stop finding jokes or amusing stories funny, even in social settings where laughter is contagious. This shift can lead to reduced participation in playful banter or an absence of the laughter that once characterized their interactions with family and friends.

In group gatherings, a person might remain stone-faced during jokes, fail to respond to lighthearted teasing, or seem confused by comedic television shows or movies. They may no longer tell jokes themselves or react with amusement to situations they previously found entertaining. This change is distinct from normal variations in mood or temporary preoccupation, as it tends to be persistent and noticeably different from the person’s prior disposition.

Caregivers and loved ones should note when a person’s sense of humor fades or laughter becomes rare, especially if this loss accompanies other cognitive or personality changes. The Alzheimer’s Society highlights that diminished humor and emotional responsiveness can indicate early cognitive decline, warranting professional evaluation and supportive social engagement strategies.

42. Over-Reliance on Family or Caregivers

Over-reliance on family members or caregivers is a notable early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, often emerging as subtle dependence on others for tasks the individual once managed independently. As cognitive abilities decline, people may seek increased assistance with everyday activities—such as managing appointments, making phone calls, organizing medication, or handling financial matters. This reliance goes beyond occasional help and becomes a regular aspect of daily life.

For example, a person may repeatedly ask a spouse or adult child to remind them about meals, accompany them to familiar places, or handle simple chores like grocery shopping or bill payments. They might express anxiety or confusion when left alone or become distressed if routines are interrupted. This growing dependence can be especially noticeable if the individual was previously self-sufficient or prided themselves on their autonomy.

Caregivers and family members should be alert to the point at which providing help transitions from occasional support to frequent or constant involvement. The Alzheimer’s Association recommends seeking a professional assessment if increased reliance interferes with independence or strains relationships, as early intervention and planning can help maintain quality of life for both the individual and their caregivers.

43. Difficulty Reading or Writing

Difficulty reading or writing is a frequently overlooked but important early sign of Alzheimer’s disease. This change arises from disruptions in the brain’s language processing centers, affecting the ability to comprehend written words, formulate sentences, or organize thoughts on paper. Tasks that once felt automatic—such as reading a newspaper, following written instructions, or composing letters and emails—may become confusing and overwhelming.

For example, a person might struggle to understand the plot of a book, reread the same lines without grasping their meaning, or become frustrated when trying to write a note or email. Their handwriting may become less legible, or they might make uncharacteristic spelling, grammar, or word choice errors. These issues are more persistent than the occasional word-finding difficulty or minor spelling mistake experienced during normal aging.

Family members and caregivers should pay attention if a loved one shows new or worsening literacy struggles, frequently asks for help with reading or writing, or avoids written communication altogether. The National Institute on Aging advises that these language changes, when combined with other cognitive or behavioral symptoms, should prompt a professional evaluation to determine the underlying cause and explore supportive strategies.

44. Misinterpreting Visual Images

Misinterpreting visual images is a common early symptom of Alzheimer’s disease and is closely linked to changes in the brain’s visual processing centers. Individuals may experience visual misperceptions, causing them to confuse shadows, reflections, or patterns with real objects or people. For example, a shadow on the floor may be mistaken for a hole, or a reflection in a window could be perceived as another person standing outside or in the room.

These misinterpretations can be unsettling and may lead to unnecessary anxiety or even hazardous situations. Someone might try to pick up a spot on the carpet, avoid walking near certain areas, or become fearful of their own reflection, believing it to be an intruder. These experiences are more frequent and persistent than the occasional optical illusion or momentary confusion common with normal aging.

Caregivers and loved ones should be vigilant if visual misperceptions begin to interfere with daily activities, cause distress, or lead to unsafe behaviors. The Alzheimer’s Association emphasizes the importance of recognizing these symptoms early, as visual misinterpretations are a key warning sign of Alzheimer’s-related decline and may benefit from environmental adjustments and professional evaluation.

45. Repetitive Movements or Pacing

Repetitive movements or pacing are common early behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease, often reflecting underlying anxiety, restlessness, or a need for sensory stimulation. These repetitive motor activities can include walking back and forth along a set path, tapping fingers, rubbing hands together, or rocking in a chair. Unlike occasional fidgeting, which is brief and typically related to boredom or nervous energy, repetitive movements in Alzheimer’s are more frequent and may become a central part of the individual’s daily routine.

For instance, a person might pace from room to room for long periods, repeatedly tap or rub surfaces, or engage in the same small action over and over, sometimes without apparent reason. These behaviors can become so constant or disruptive that they interfere with daily activities, cause fatigue, or even lead to accidental injury. Attempts to redirect the individual may provide only temporary relief.

Caregivers should take note if repetitive motor behaviors increase in frequency or intensity, especially if they disrupt rest, meals, or social interaction. The Alzheimer’s Society advises that persistent or disruptive repetitive movements warrant evaluation and can often be managed by adjusting routines, increasing engagement, or seeking professional support.

46. Difficulty Differentiating Reality from TV

Difficulty differentiating reality from television or other media is an early sign of Alzheimer’s disease, resulting from altered reality testing and impaired cognitive processing. Individuals may become confused about whether events or people seen on TV are part of their real life, sometimes believing that news stories, fictional characters, or televised conversations are happening to them or their family. This confusion occurs because the brain’s ability to interpret and distinguish between real experiences and media representations deteriorates.

For example, a person may insist that a crime shown in a drama series occurred in their neighborhood, or express concern about a family member based on something seen in a commercial or documentary. They might talk as if television characters are acquaintances or mistake televised events for recent personal experiences. This misinterpretation can lead to anxiety, misplaced fears, or inappropriate responses to everyday situations.

Caregivers should be attentive to these signs and note if confusion between TV content and real-life events becomes persistent or disruptive. The Alzheimer’s Association recommends early intervention when these symptoms appear, as professional assessment and supportive strategies can help manage distress, clarify reality, and provide reassurance as the disease progresses.

47. Inflexibility with Routines

Inflexibility with routines is a frequent early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting increased cognitive rigidity and a diminished ability to adapt to new circumstances. As Alzheimer’s affects the brain’s executive functioning and flexibility, individuals may become highly reliant on established habits and struggle with even minor deviations from their preferred schedule. This inflexibility often centers around daily rituals, such as mealtimes, bedtime routines, or the order in which tasks are performed.

For example, a person may insist on eating the same foods at the same time each day, become upset if their usual seat at the table is taken, or resist bathing or dressing at a different time. Attempts to introduce new activities, adjust schedules, or change the sequence of daily tasks can provoke anxiety, irritability, or outright refusal. This resistance is more pronounced than a typical preference for routine and can interfere with caregiving or family life.

Caregivers and family members should observe for signs of distress or agitation when routines are altered, as these reactions may indicate underlying cognitive decline. The Alzheimer’s Society provides guidance on gently supporting flexibility and adapting routines to minimize distress for individuals living with Alzheimer’s disease.

48. Becoming Easily Distracted

Becoming easily distracted is a common early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, attributed to the brain’s decreasing ability to maintain attention and filter out irrelevant stimuli. As the condition impairs cognitive control, individuals may find it increasingly difficult to focus on tasks, conversations, or activities for extended periods. This reduced attention span can lead to incomplete projects, frequent topic changes, and a general sense of restlessness.

For example, during a conversation, a person may abruptly shift topics, lose their train of thought, or become preoccupied with background noises or visual distractions. They may start a household chore only to abandon it moments later, or repeatedly forget what they were doing mid-task. Unlike mild distractibility that everyone experiences occasionally, Alzheimer’s-related attention deficits are persistent and can significantly impair daily functioning and independence.

Caregivers and loved ones should note when loss of focus becomes prominent—such as missed steps in meal preparation, difficulty following multi-part instructions, or trouble keeping track of appointments or conversations. The National Institute on Aging highlights persistent distractibility and attention problems as early warning signs of Alzheimer’s, recommending professional assessment when these issues begin to affect daily life.

49. Overlooking Personal Safety

Overlooking personal safety is a significant early behavioral change in Alzheimer’s disease, rooted in declining judgment and impaired risk assessment. As the brain’s decision-making abilities are compromised, individuals may fail to recognize or respond to potentially dangerous situations in the home or community. This can result in lapses that put themselves or others at risk, even when they previously demonstrated strong safety awareness.

Examples include forgetting to turn off the stove after cooking, leaving doors or windows unlocked, misusing household appliances, or venturing outside without appropriate clothing or identification. A person might leave water running, neglect to check for hot surfaces, or attempt to drive despite confusion or disorientation. These oversights are more frequent and concerning than typical forgetfulness or momentary distractions, as they can lead to accidents, injuries, or emergencies.

Caregivers and loved ones should closely supervise individuals showing signs of compromised safety and assess the need for environmental modifications, such as stove guards or door alarms. The Alzheimer’s Association provides guidance on adapting living spaces and routines to reduce risks, and recommends seeking professional input when safety lapses become noticeable or recurrent, ensuring ongoing well-being and security.

50. Trouble Recognizing Own Symptoms

Trouble recognizing one’s own symptoms, known as anosognosia, is a frequent and particularly challenging early feature of Alzheimer’s disease. This lack of awareness means individuals may genuinely fail to perceive their cognitive or behavioral changes, often minimizing, denying, or rationalizing forgetfulness, confusion, or other issues. Anosognosia occurs because the disease affects brain areas responsible for self-monitoring and insight.

For example, a person may insist that their memory is normal, dismiss repeated reminders, or become defensive when concerns are raised about their ability to manage daily tasks. They might attribute missed appointments or lost items to external factors, or simply laugh off mistakes. This unawareness is distinct from intentional denial; it is a neurological symptom, not a conscious choice.

Because anosognosia can delay diagnosis and intervention, it is essential for loved ones and caregivers to remain observant and, when appropriate, gently involve healthcare professionals. Early assessment is crucial for accessing treatment, support, and planning for the future. The National Institute on Aging offers detailed information about anosognosia, emphasizing the importance of family involvement and professional evaluation when a person appears unaware of their symptoms.

Conclusion

Recognizing early behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease is vital for timely intervention and improved quality of life. Subtle shifts in memory, judgment, mood, or daily routines can be the first indicators of cognitive decline. By paying close attention and acting on these signs, families and caregivers can facilitate earlier diagnosis, access helpful resources, and plan appropriate support. Early intervention offers the greatest potential to slow disease progression and maintain independence. If you observe persistent or worsening symptoms, consult a healthcare professional or explore screening tools from reputable organizations like the Alzheimer’s Association to ensure prompt assessment and guidance for the journey ahead.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider with any questions about symptoms or health concerns. See the National Institute on Aging for more guidance.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for general informational purposes only. While we strive to keep the information up-to-date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability, or availability with respect to the article or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained in the article for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this article.

Through this article you are able to link to other websites which are not under our control. We have no control over the nature, content, and availability of those sites. The inclusion of any links does not necessarily imply a recommendation or endorse the views expressed within them.

Every effort is made to keep the article up and running smoothly. However, we take no responsibility for, and will not be liable for, the article being temporarily unavailable due to technical issues beyond our control.